Blog

Martin-Guillaume Biennais

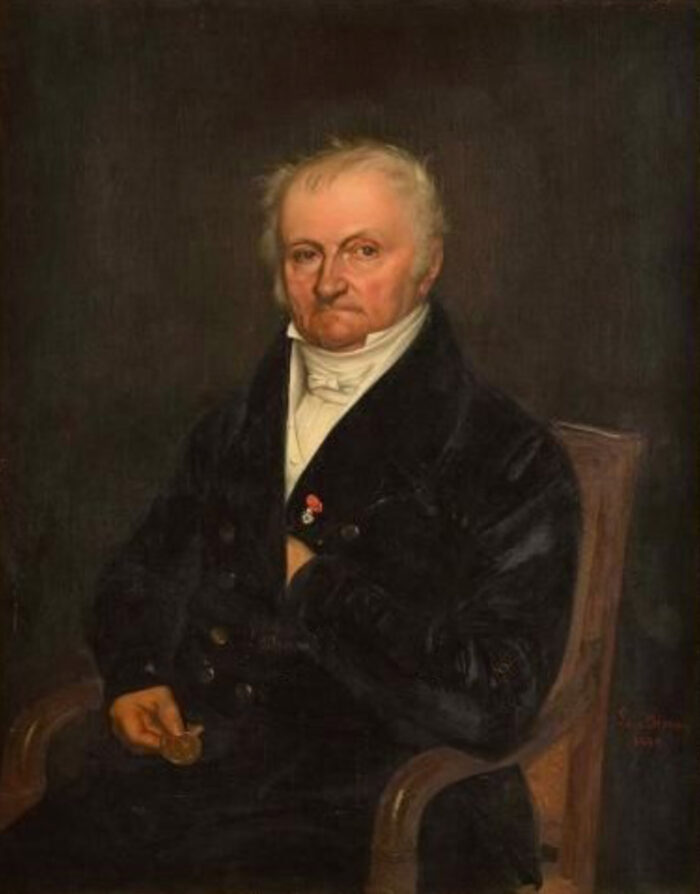

Martin-Guillaume Biennais was born in the Normandy region of La Cochère, France in 1764. His early years were dedicated to training as a craftsman, before moving to Paris at the age of 24. There, he specialised as a tabletier (a manufacturer of small luxury and decorative items from wood or ivory), an ébéniste (a cabinet-maker, particularly working with Ebony) and an orfévre (a goldsmith).

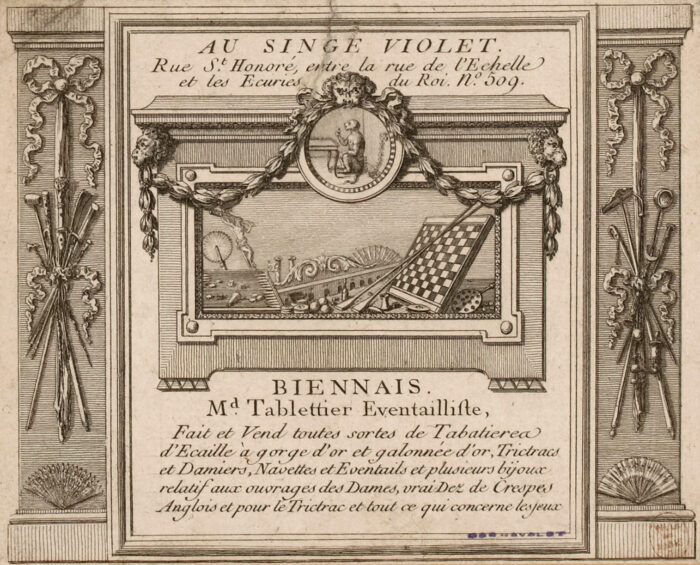

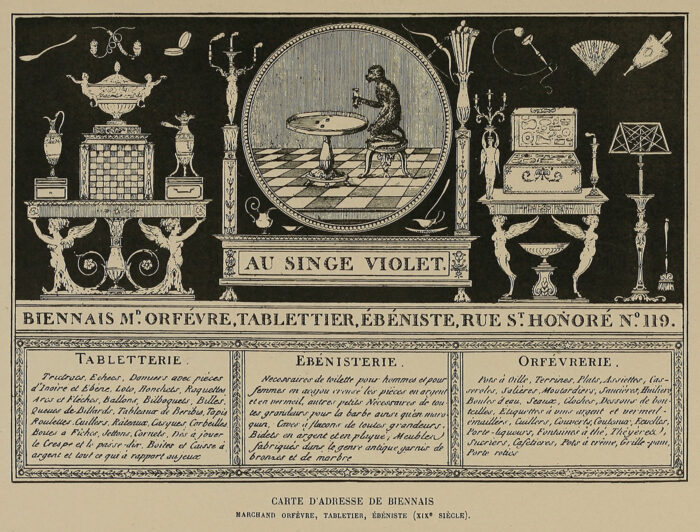

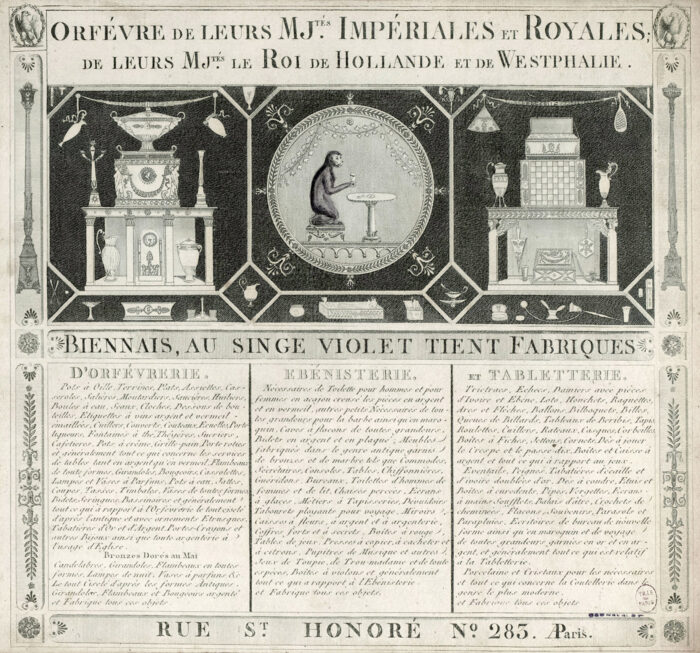

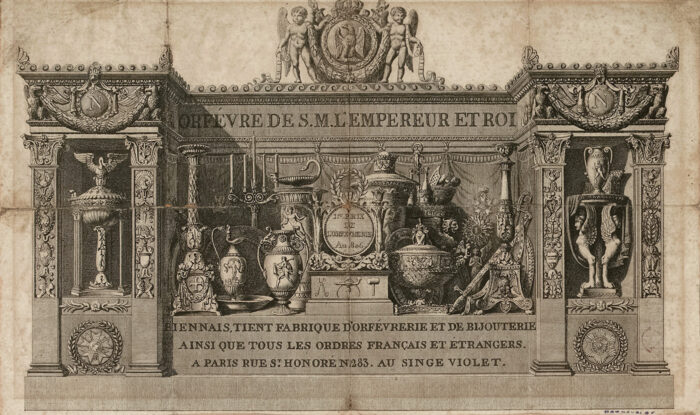

In 1789, Biennais set up his own establishment at Au Singe Violet (at the [sign of the] purple monkey), 509, 510 & 511 Rue Saint-Honoré, Paris. In 1790 the shop numbers were changed to 119 & 121 Rue Saint-Honoré, then changed again in 1805 to 281 & 283 Rue Saint-Honoré.

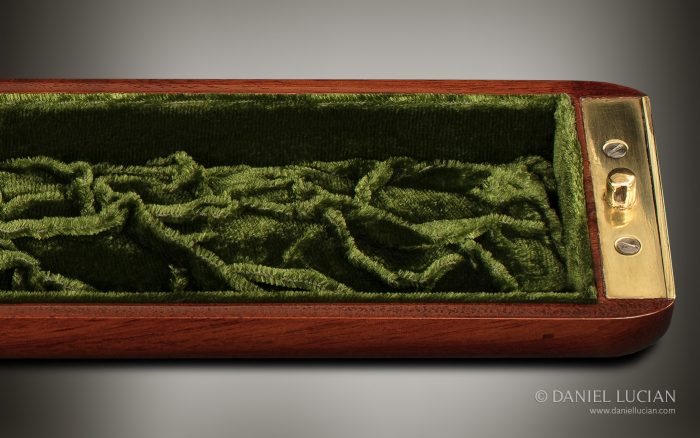

One of Biennais’ particular specialities was the manufacture of travelling nécessaire boxes, often crafted from solid mahogany; he employed freelance silversmiths to populate their interiors with bottles, jars and all manner of ‘necessary’ tools and instrumentation to accompany their owners during travel. At this time, the demand for luxury goods was very minimal, but Biennais’ work supplying nécessaires to French army officers reliably sustained his business. With the dissolution of workers’ guilds and associations under the Le Chapelier Law of 1791, merchants and artisans were now allowed to work as individuals free from their former practice restraints; as a result, Biennais expanded his business repertoire by being able to manufacture and certify silver items in-house.

In 1798, just prior to Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign to Egypt and Syria, Biennais supplied Napoleon with some nécessaires on credit with the agreement that the debt was to be repaid upon his return. As good as his word, Napoleon did indeed pay what he owed. Whilst the work of Biennais was exceptional in its own right, it seems that the faith and trust he exhibited towards Napoleon also favoured him well; in 1804, Biennais was made the imperial goldsmith, supplying the crown, sceptre and other ceremonial adornments for Napoleon’s coronation in December of that same year.

At the height of his success, having built up an exclusive client base to include the French imperial and royal family, the King and Queen of Holland, the King of Westphalia, and the royal households of Russia, Austria and Bavaria, Biennais was employing nearly 200 artisanal workers.

In 1819, Biennais retired, leaving his business to his former apprentice, Jean-Charles Cahier.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais died at his home in Paris in 1843 at the age of seventy-eight.

Today, the magnificent works of Biennais are rare, but can be found in some of the most renowned museums, royal households, stately homes and private collections around the world.

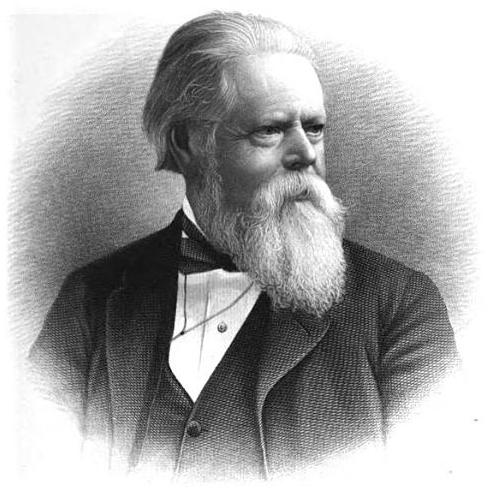

Martin-Guillaume Biennais (1764-1843).

Martin-Guillaume Biennais advertisement/ letterhead from 1789 within his first year of business. Note the address number of 509; the shop numbers were changed to 119 & 121 in 1790, so we are able to accurately date this.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais advertising business card from circa 1795.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais invoice letterhead from 1805.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais invoice letterhead from 1811.

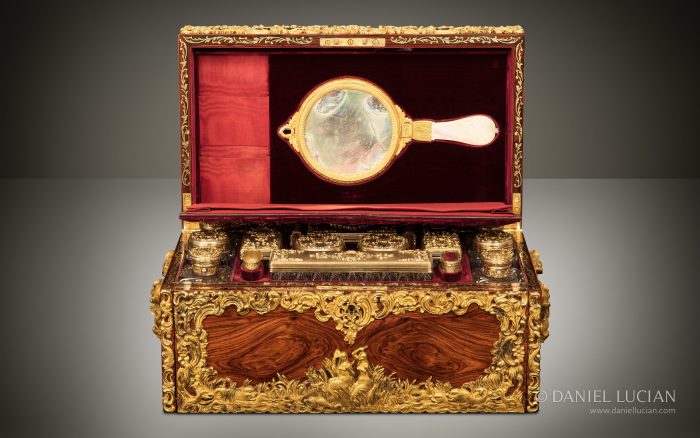

This is largest of all Napoleon I’s nécessaires manufactured by Biennais around 1802. The silver-gilt contents had originally been engraved with a ‘B’ for Bonaparte, but this was replaced with the Emperor’s coat of arms in 1807.

Necessaire de voyage belonging to Napoleon I, manufactured by Martin-Guillaume Biennais.

Rack and Pinion Mechanical Box

This antique box is a mechanical prototype that was manufactured under a commission by Queen Victoria during the mid-1840’s.

From first viewing the closed box, one can see that this is indeed something special, but then a few questions arise; what are those engraved brass mounts that look like side handles but aren’t, and what accounts for its near 12kg in weight?

We must open the box and begin to investigate; immediately one’s eyes focus on the network of engraved brass rims with Queen Victoria’s VR initials and crown as a centrepiece, and four curious apertures marked fast and slow. However, it’s those two unusually large brass push buttons on the rear rim of the box that really intrigue above all else.

View of the large brass push buttons on the rear rim of the box and the ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ adjustment points (bottom left).

The left-hand push button:

This initiates a sequential movement of sliding steel mitred bars within a system of brass rails that enable the simultaneous retraction of catches to the left and right side walls of the box; this allows the two side trays to slide out automatically. These trays run on individual rack and pinion mechanisms; a spiral torsion spring within each pinion unwinds in order to propel the tray outwards.

View of the rack (steel linear toothed gear) and pinion (brass circular toothed gear) mechanism. The pinion is internally spring-loaded using a spiral torsion spring.

Another question arises; what is the intended purpose of these most unusual slow and fast adjustment points to each tray? From the surface, one can only see a square threaded shaft through each of the apertures. However, beneath the surface is a screw thread, with a rectangular nut and coiled spring to the end; using its dedicated key, this can be wound up or down to regulate the tension on the spring and, thus, create friction against a steel plate that runs under the tray. It is this friction that is used to slow down or speed up the sliding action of the tray.

View of the ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ adjustment point with key inserted.

Both trays are fitted with their own spring-loaded secret drawers that are deployed by pressing a concealed trigger in the floor above.

The right-hand push button:

This retracts a centrally mounted steel catch that allows four pairs of steel leaf springs to lift the central brass platform into its fully raised position. The platform has been strategically fretworked to display the mechanism beneath whilst maintaining maximum structural strength at the points where the platform and mechanism interact.

View of a pair of steel leaf springs. The mechanism uses four pairs of these leaf springs to lift the central brass platform.

This box was primarily built to serve as a prototype and, as much as it is an object of beauty in its own right, it seems to be more about showcasing the manufacturer’s engineering excellence, ingenuity and creativity with the hope of impressing this most important of clients.

It is rather astonishing to consider that this box predates the mechanically innovative work of George Betjemann & Sons by at least twenty years, so it is particularly frustrating that this piece was left unsigned.

Everything about this box is extravagant; it’s over-engineered, unnecessarily complicated, excessively powerful in its operation, and almost too heavy duty in build quality for its intended purpose… but what a visual feast of mechanics!

Amboyna

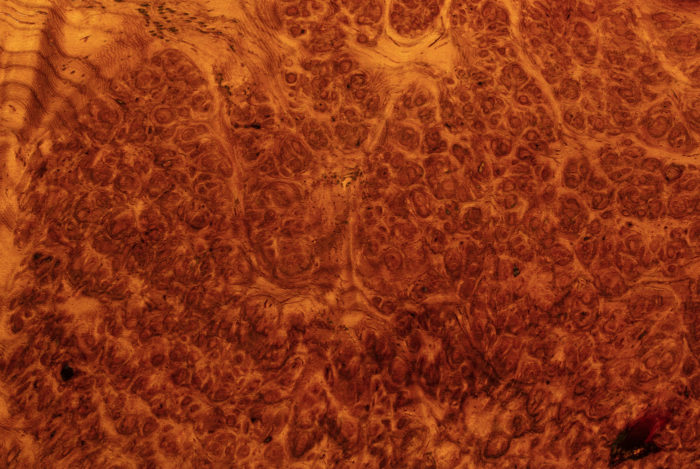

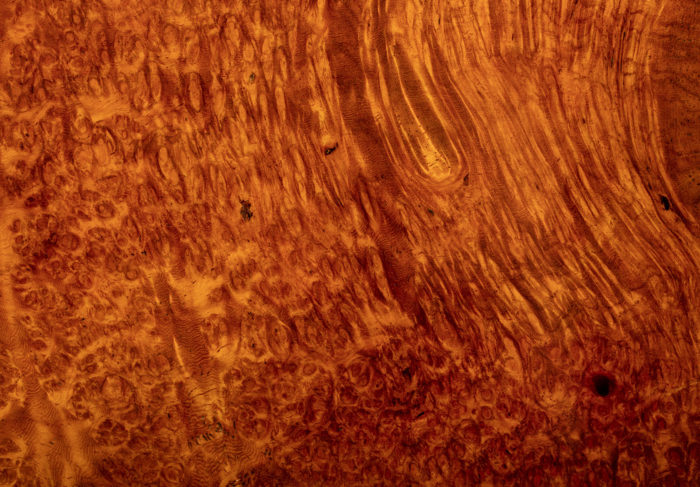

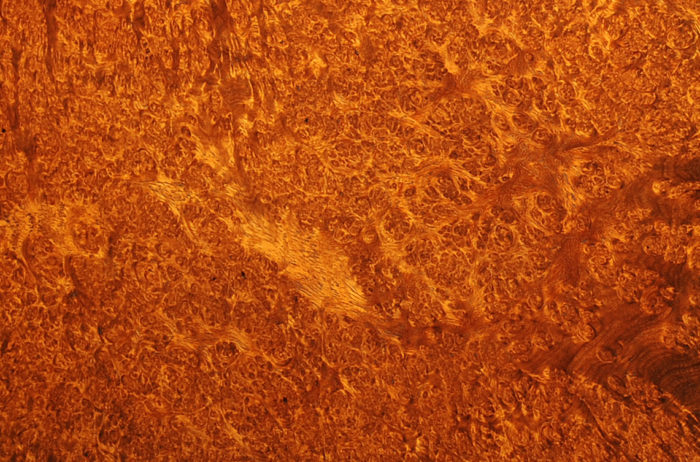

Often confused with Thuya wood or Burr Walnut, Amboyna is a profusely burred wood that is a part of the Pterocarpus genus, most commonly obtained from the Narra Tree (Pterocarpus indicus), and is native to Southeastern Asia, Northern Australasia, and the Western Pacific Ocean islands. The name Amboyna is derived from the Ambon Islands in Indonesia, where it is believed that this wood was first sourced and exported.

Due to its attractive figuring, Amboyna is a particularly rare and desirable wood for furniture and box manufacturing; within a single piece, its figuring can be quite diverse, from tight clusters of burrs to lighter, flowing and rippled areas that appear almost three-dimensional. Amboyna’s colour characteristics can range from a yellowy-honey colour to an almost reddish Mahogany colour.

Amboyna veneer from an antique jewellery box.

Amboyna veneer from an antique jewellery box.

Amboyna veneer from an antique jewellery box by Howell, James & Co.

F. L Hausburg

Friedrich Ludwig Hausburg was born in Berlin, Prussia in 1817. He began his career working alongside his uncle, August Wilhelm Bernhardt Promoli, based at 4 Rue de Boulogne, Paris, specialising in fine jewellery, clocks and a wealth of other luxury items.

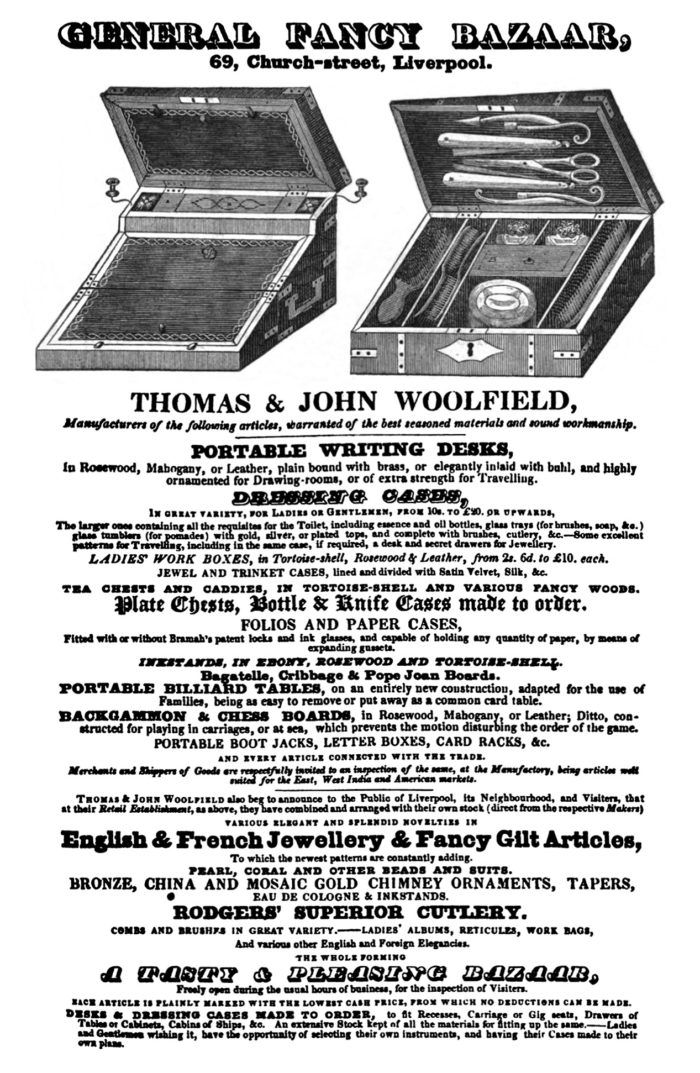

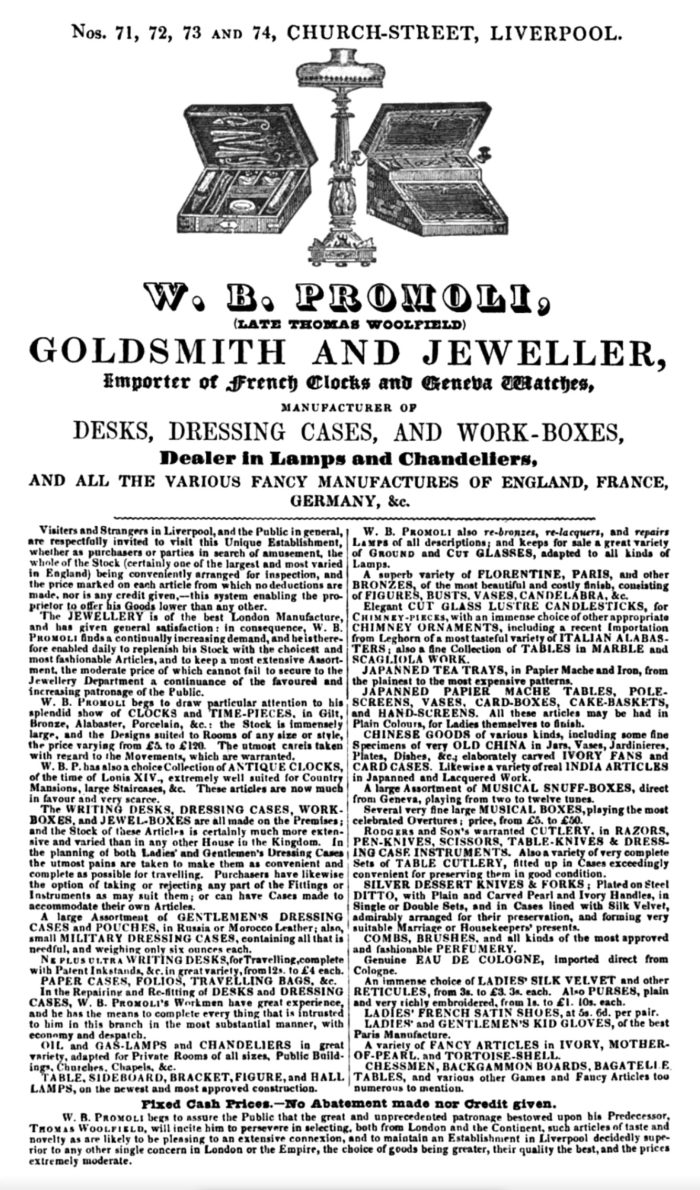

An advertisement from Pigot & Co’s National Commercial Directory confirms that Promoli had taken over the business of Thomas Woolfield by 1837. Woolfield was the uncle, by marriage, of Hausburg’s wife, Catherine Mossop; he was predominantly a writing and dressing case manufacturer, but also retailed a vast array of fancy goods. Having been previously known as Woolfield’s Bazaar, based at 71 & 72 Church Street, Liverpool, the business was now titled as W. B Promoli and had expanded to 71, 72, 73 & 74 Church Street.

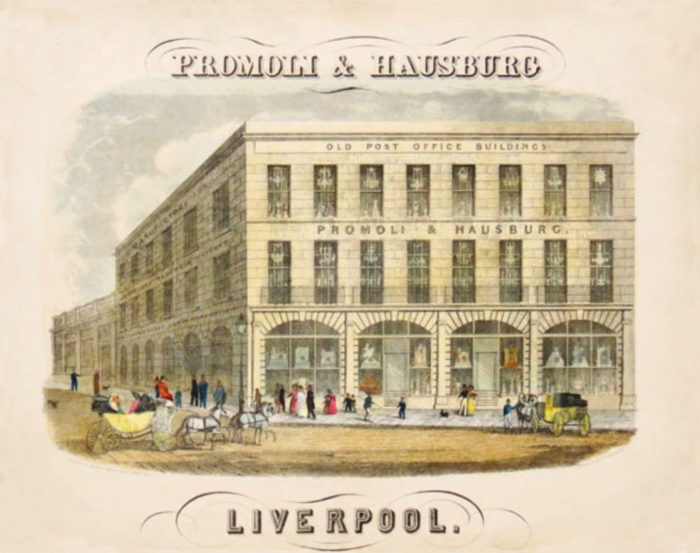

In August 1840, both Hausburg and Promoli were naturalised as British citizens; a legal act that could not only boast having Queen Victoria as its personal signatory but that, uniquely, was passed in just five weeks instead of a usual four years. That same year the name of the business was changed to Promoli & Hausburg, with their address now declared as Old Post Office Buildings, 24 Church Street, Liverpool. Together, they advertised themselves as ‘Jewellers, Watchmakers, Manufacturer’s of Desks, Dressing Cases, Lamps and Chandeliers’.

Just a year later in 1841, the business was solely in the hands of Hausburg who continued dealing in the same vast range of luxurious inventory.

Looking at Hausburg’s work, one can clearly see the French influences harking back from when he was working in Paris; whilst very well versed in the more ‘reserved’ British style of exterior case design, he often produced pieces that featured far more lavish and intricate inlay work. Hausburg was known to use materials such as brass, pewter, ivory, abalone and mother of pearl to inlay into woods, or produce pieces dressed with Boulle work (tortoiseshell inlaid with brass). These decorative influences were often also applied to the interiors of his cases, with the inclusion of elaborately gold tooled leather to line the walls, floors, trays, and other components.

Hausburg retired in 1860 at the age of 43, selling his business to W.H Tooke who continued it from the same address. When Hausburg died in 1886, his estate was valued at a staggering £180,000 (£24 million in today’s money).

There is a wonderful, if not a little manic, article entitled ‘A Fashionable Shop At Liverpool’ written by a New York journalist, taken from the The Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review – June 1849, Vol. XX, No. VI; this journalist is in a state of rapture and trying, or rather struggling, to accurately make sense to his readers [and, I must assume, himself] just exactly what he has experienced after having visited Hausburg’s establishment,

“It must not for a moment be confounded with those receptacles of low-priced and slop-manufactured articles, commonly called bazaars, where there is much glitter and show, much tinsel and gay color, but little solid and substantial value. Presenting infinitely more variety than the best or more extensive of the marts just alluded to, it ranks above them in a degree that will not admit of the slightest comparison in the richness, rarity, beauty, and we may, with propriety, say splendor, of the articles offered for inspection. Indeed, I should not have written the word bazaar in connection with it but for the purpose of preventing any mistake or comparison of ideas in the mind of my readers. It bears about the same relation to a bazaar that a costly jewel, tastefully mounted in fine gold, does to a glittering gewgaw of paste set in Dutch metal. It wants an appropriate designation, for it is so completely unique that no ordinary term will serve to convey to the mind any notion of its extent, appearance, or purposes. I cannot call it a shop or a store without conveying an inappropriate image or false impression.I have seen the magnificent shops of London and Paris, and there are some fine shops, too, in Liverpool, but this establishment is so entirely different from them that the designation would be utterly inappropriate. As to ordinary shops, it is as infinitely superior to them as a palace is to a cottage.“

An Illustration from 1840 of Promoli & Hausburg’s emporium, manufactory and warehouse based at Old Post Office Buildings, 24 Church Street, Liverpool.

F. L Hausburg manufacturer’s mark gold tooled onto leather from an 1852 antique dressing case in burr walnut.

Thomas & John Woolfield advertisement taken from Pigot & Co’s National Commercial Directory, For 1828-9.

W. B Promoli (late Thomas Woolfield) advertisement taken from Pigot & Co’s National Commercial Directory, For 1837.

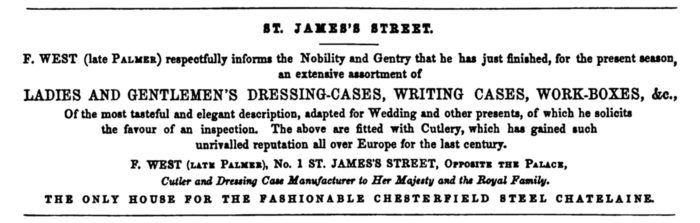

F. West

Fitzmaurice West established himself as a cutler and dressing case manufacturer in 1839. It is likely that West was a former employee of George Palmer, also a cutler and dressing case manufacturer, and they shared a premises based at 1 St James’s Street, London. Although Palmer continued working at this address until at least 1842, records and advertisements from 1840 show that West declared his business as ‘late Palmer’; this would indicate that although they were still sharing an address, they were now two separate businesses.

West became one of the appointed manufacturers to Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, the Duchess of Kent and other members of the Royal Family.

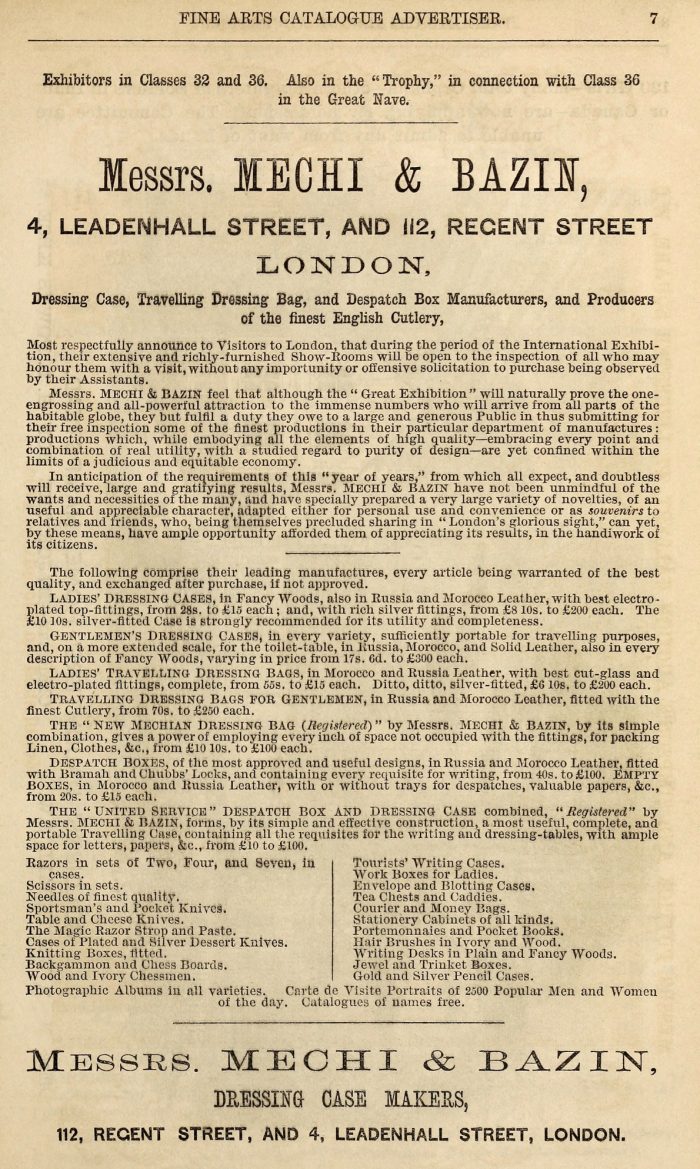

West exhibited his dressing cases, writing cases and travelling bags at the International Exhibition of 1862. Along with fellow dressing case manufacturer Charles Bazin, West was on the panel of jurors for the International Exhibition presiding over the category of ‘Dressing Cases, Despatch Boxes and Travelling Cases’. This position precluded West from having his own exhibits judged, however the following was documented in the ‘International Exhibition 1862 – Reports By The Juries On The Subjects In The Thirty-Six Classes Into Which The Exhibition Was Divided’ (Peter Le Neve FOSTER, John Frederick ISELIN (the Elder) 1863), “The Jury consider it a duty to state their opinion with respect to the collections exhibited by Mr. F. West and Messrs. M. & B. [Mechi & Bazin], and to declare that, but for the exceptional and honourable position which they hold, they would have placed them in the first order of merit”.

West moved his business to 2 St James’s Street, London in 1877 and later, in 1883, to 9 King Street, St James’s, London.

As a side note, it is interesting to observe that many of West’s dressing cases were finished with ebony veneer and contrasted with brass work. This was a relatively unusual veneer choice for an English dressing case, and it is indeed possible that West was inspired by his French contemporaries, who often adopted this ebony and brass combination for their nécessaires.

F. West advertisement taken from The Stowe Catalogue, 1848.

‘F. West – Manufacturer To Prince Albert & The Royal Family – No.1 St James’s St.’ engraved brass manufacturer’s plate from an antique dressing case in coromandel with silver fittings, by Fitzmaurice West.

Bramah Locks and Keys

The complete Bramah lock can be disassembled into the following parts: READ MORE

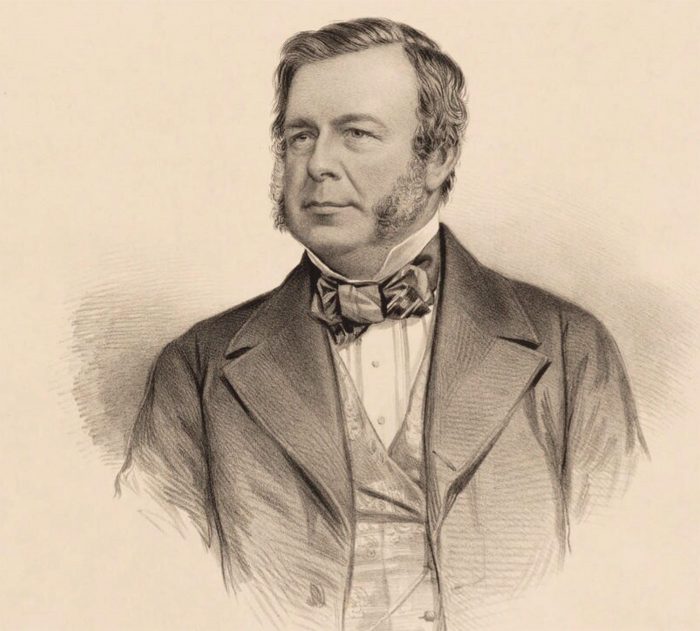

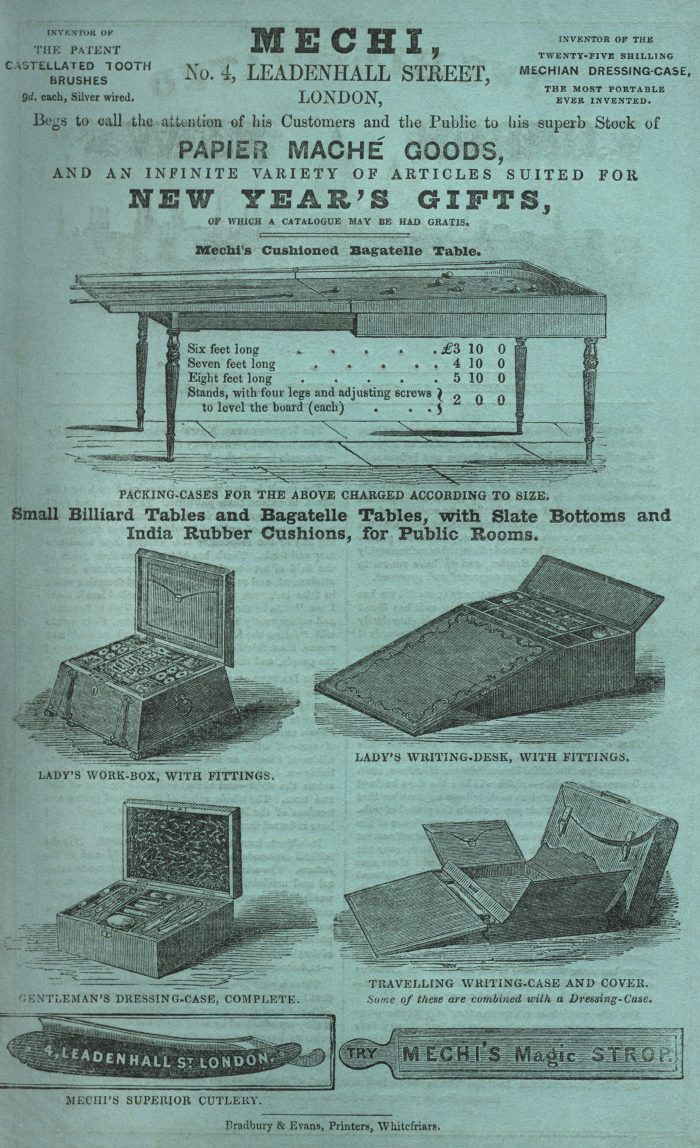

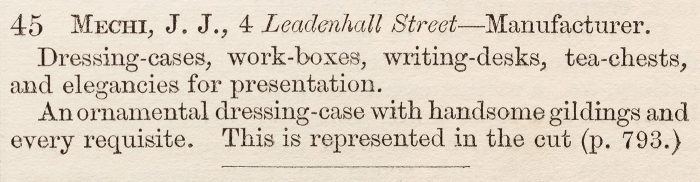

Mechi

Of Italian descent, John Joseph Mechi was born in London in 1802. From savings amassed over a ten year period from his job as a clerk, in 1827 Mechi started his own business as a cutler from 130 Leadenhall Street in the City of London.

In 1830, he moved to a larger premises at 4 Leadenhall Street. Whilst Mechi manufactured a vast array of necessities and luxury items, his Magic Strop (an instrument to maintain and sharpen cutthroat razors) is what made him extremely successful and wealthy. Mechi was a master self-promoter, and his – often over-elaborately written – advertisements were prevalent in the English periodicals.

Despite being a very talented cutler his passion was for farming; in 1841 Mechi bought a large failing farmland estate in Essex which he rebuilt and, by applying his own advanced methods and techniques as well as a great deal of money, turned it into a model farm that he renamed Tiptree Hall. This became a very profitable enterprise and Mechi was soon renowned as an agricultural expert, publishing a significant amount of literature and demonstrating his practices and machinery for the many hundreds of visitors to his farm each year.

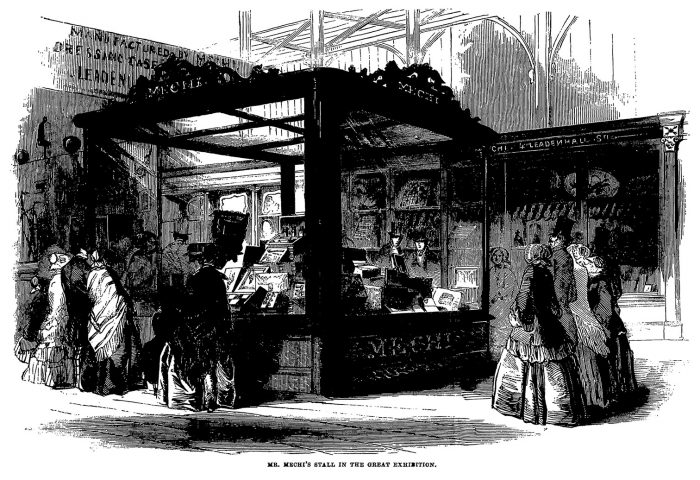

Through his membership of the Society of Arts, Mechi became a juror for the art and science department at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855. Although his duties precluded him from competing for awards at the Great Exhibition, Mechi displayed an assortment of his wares to great fanfare, including dressing and writing cases, work boxes and even a working model of his Tiptree farm.

Ironically Mechi’s fortunes were made and lost because of the beard. Up until the Crimean War (1854-56), the fashion for gentlemen was a clean-shaven appearance. Despite beards being banned in the army, the freezing temperatures experienced by the soldiers on the Crimean peninsula along with the inability to get shaving provisions negated this rule. Soldiers returning from war sporting their beards inspired a brand new and largely adopted fashion that was now synonymous with heroism. Mechi’s razors and ‘Magic Strops’ were no longer of interest and business plummeted with an almost immediate effect. The timing was particularly dire as Mechi had recently expanded his business in 1855 with further locations at 112 Regent Street, and at the Crystal Palace, Sydenham. [The ‘Crystal Palace’ was the venue for the 1851 Great Exhibition, and was dismantled and rebuilt in Sydenham in 1854].

In 1856, Mechi became the governor of the Unity Joint Stock Mutual Banking Association as well as being appointed a Sheriff of the City of London. Moving up a rung on the political ladder, Mechi was elected as Alderman of Lime Street Ward, City of London in 1858.

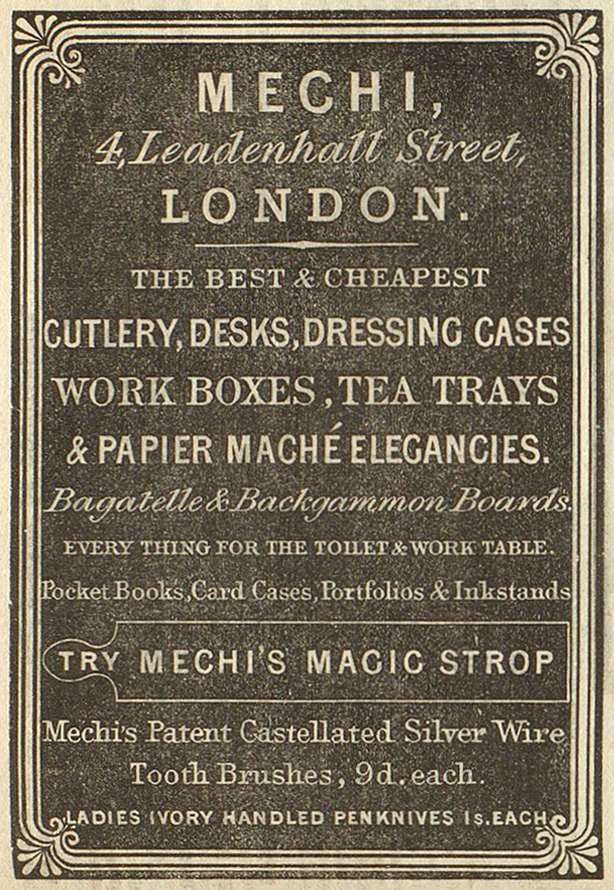

Charles Bazin had worked with Mechi since 1838 and was a skilled cutler in his own right; for all intents and purposes he had single-handedly run the retail business whilst Mechi was turning his attention to his political career. In respect for Bazin’s twenty-one years of loyal support, Mechi made him a partner in the business in 1859; accordingly the business name changed to Mechi & Bazin.

Mechi & Bazin displayed a selection of their dressing cases, despatch boxes and writing table sets at the International Exhibition of 1862. Due to Bazin being one of the jurors for the ‘Toilet, Travelling, and Miscellaneous Articles’ class, Mechi & Bazin were precluded from the award assessments.

When Charles Bazin died in 1865, at the age of 40, the ownership of the business transferred back to Mechi. The 4 Leadenhall Street location was closed and the entirety of the business was moved to his Regent Street address. However it wasn’t until 1869 that the name of Mechi & Bazin officially reverted to Mechi’s own.

Mechi was an extremely well-known, determined and relentless character; his past business failures had never meant the end, they merely signified a time for necessary reinvention. However his life and fortunes permanently changed with the collapse of the Unity Joint Stock Mutual Banking Association in 1866 for which he was found chiefly responsible. As a result, he lost £30,000 [approximately £3.4 million in today’s money] from his own coffers and felt compelled to resign from his Aldermanic post and from his running for Lord Mayor of London.

On the 14th December 1880, Mechi’s retail and farming businesses were put into liquidation, with Mechi, a now broken man, dying just 12 days later on Boxing Day.

John Joseph Mechi (1802-1880).

Illustration of Mechi’s shop at 4 Leadenhall Street, London taken from his catalogue entitled, ‘List of Articles Manufactured and Sold – Wholesale, Retail, and for Exportation, by Mechi, No.4 Leadenhall Street, London.’

A Mechi advertisement taken from Charles Dickens’ serialised version of ‘Martin Chuzzlewit’ from January 1844.

An illustration of Mechi’s stand at the Great Exhibition of 1851 taken from the ‘The Lady’s Newspaper’, September 6th 1851.

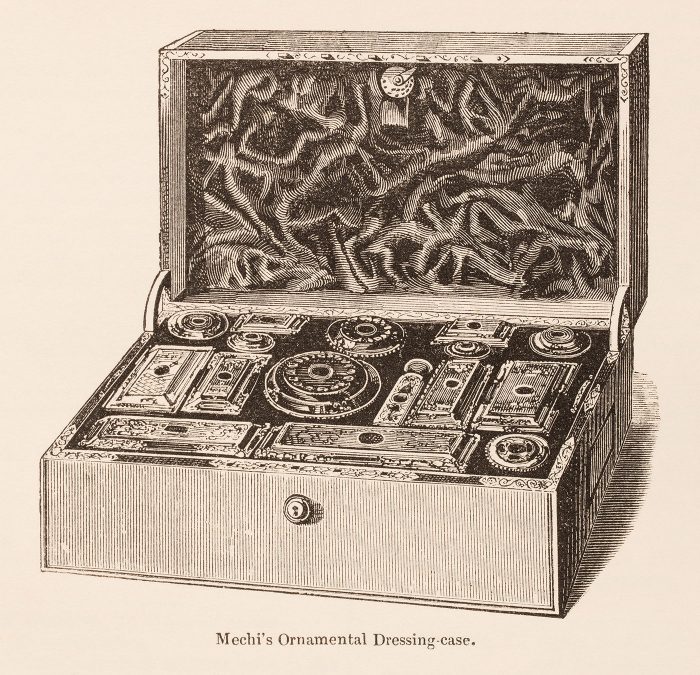

An illustration of Mechi’s ornamental dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

A description of Mechi’s ornamental dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

A Mechi advertisement taken from Charles Dickens’ serialised version of ‘Bleak House’ from March 1852.

A Mechi & Bazin advertisement taken from the ‘International Exhibition 1862 Official Catalogue of the Fine Art Department’.

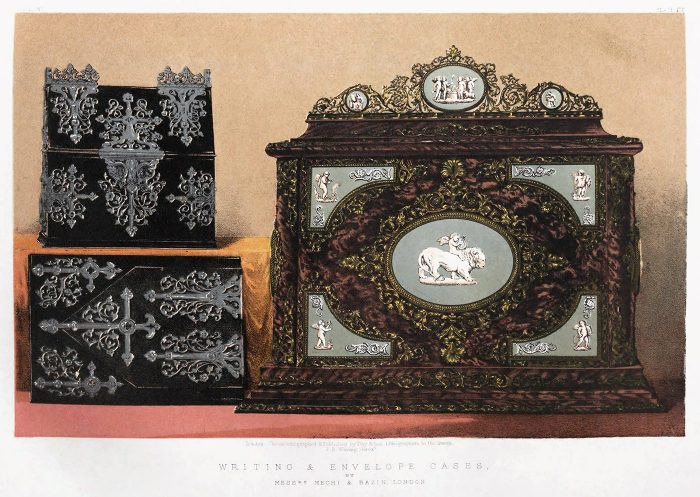

An illustration of writing and envelope cases by Mechi & Bazin taken from the ‘Masterpieces of Industrial Art & Sculpture at the International Exhibition, 1862’ by J.B Waring.

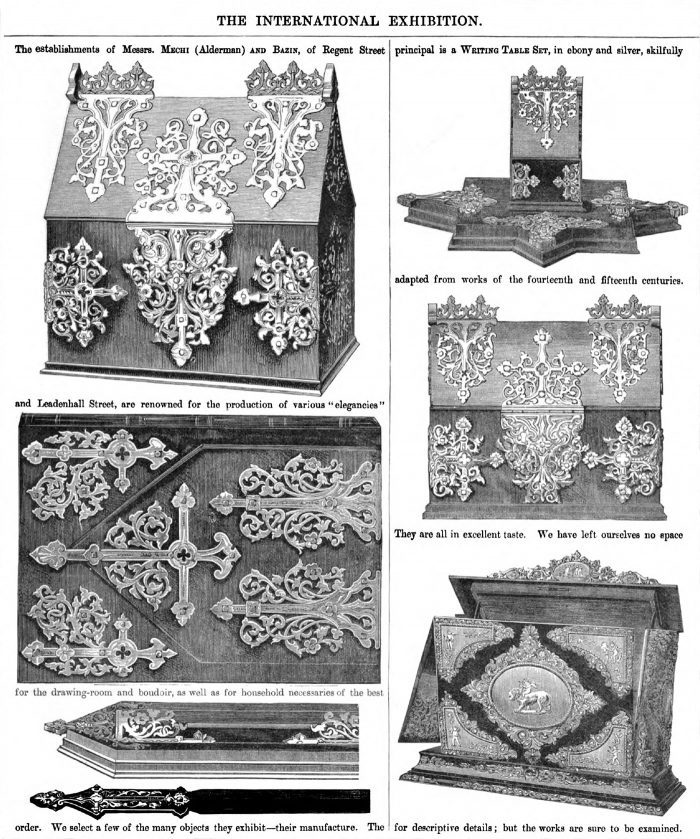

An illustration of a writing table set by Mechi & Bazin taken from ‘The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition 1862’.

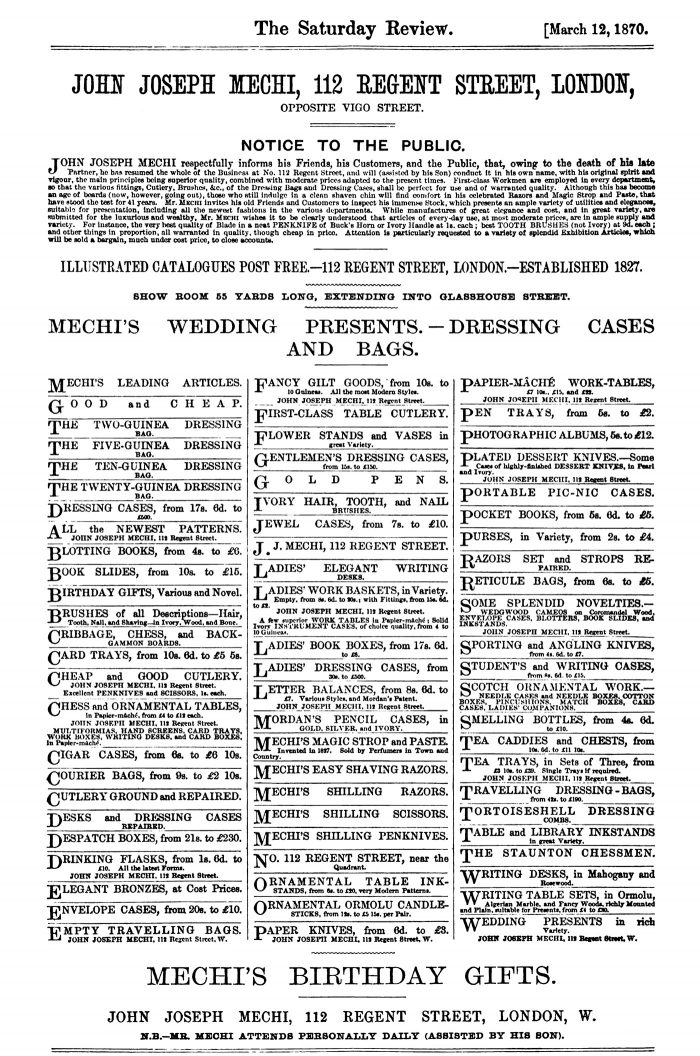

A Mechi advertisement taken from ‘The Saturday Review’ on March 12th 1870.

A Mechi & Bazin engraved brass manufacturer’s and retailer’s plate.

Gold Tooling and Leather Tooling

Very much associated with bookbinding, gold tooling is the method of impressing lettering or a decorative design, through a sheet of 22 or 23 karat gold leaf, onto a leather, paper or cloth surface. ‘Blind’ tooling is an almost identical technique but without the addition of gold leaf. READ MORE

Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’

If a lock with 12 sliders has a 1 in 479 million chance of being opened without its dedicated key, and then by adding just one more slider raises that probability to 1 in 6.2 billion – how on earth does someone successfully pick a lock with 18 sliders? This is the story about a challenge that had remained unanswered for over 60 years, and the charismatic American that seemingly achieved the impossible. His actions would bring insecurity all the way up to the highest establishments of England. This unusual series of events that took place in 1851 became known as the Great Lock Controversy.

Joseph Bramah set up his locksmithing business at 124 Piccadilly, London in 1784. The technical achievement and level of security offered by Bramah’s locks were considered far beyond anything presented by his peers. As a result, the demand for his locks greatly outweighed his ability to manufacture them. Bramah needed to find a way to produce these locks in larger numbers, make them more economical to manufacture and, improve and standardise their quality. The solution came in 1789, when Bramah hired Henry Maudslay upon the recommendation of his employees. Maudslay was only 18, but his technical and mechanical abilities impressed Bramah to such a degree that he soon became his chief engineer. The collaboration of both Bramah and Maudslay produced a set of precision tools and machinery that addressed all of Bramah’s previous issues.

Joseph Bramah (1748 – 1814).

Henry Maudslay (1771 – 1831) – Chief Engineer at the Bramah Lock Company from 1789 – 1797.

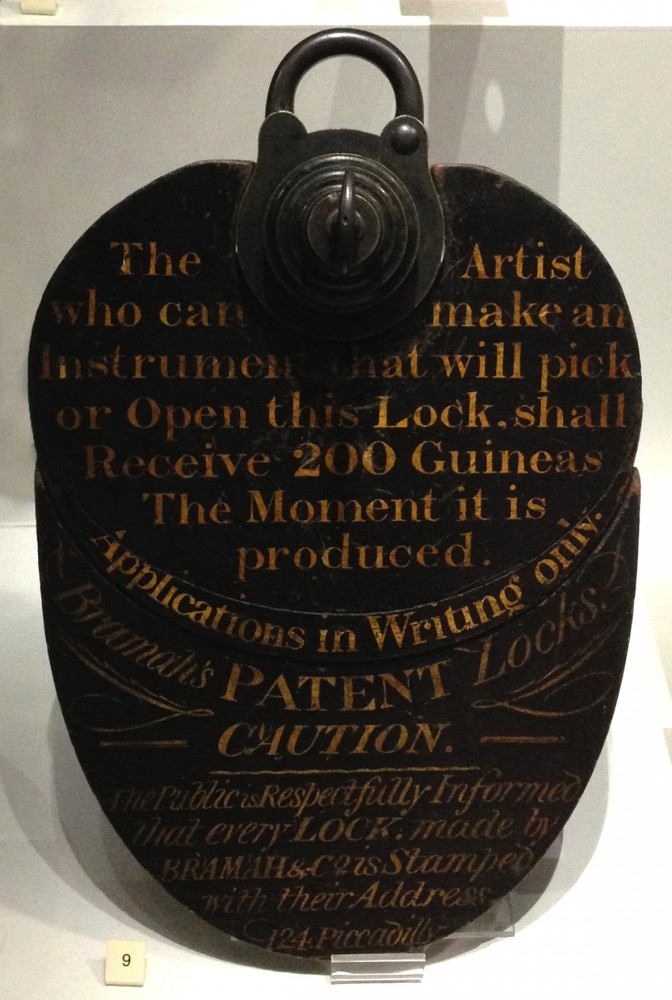

In 1790, Maudslay was instructed to manufacture a padlock so secure and un-pickable that it couldn’t be opened by any means other than with its own dedicated key. With overwhelming confidence, Bramah mounted the padlock, placed it in his shop window and issued a challenge: in gold lettering upon a black background, he stated, ‘The artist who can make an instrument that will pick or open this lock shall receive 200 Guineas [approximately £30,000 in today’s money] the moment it is produced’.

Recreation of Bramah’s shop front at 124 Picadilly, London, with the ‘Challenge Lock’ on display, taken from the Science Museum in London.

Joseph Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’ mounted within its challenge board, as displayed in his shop window from 1790. Now displayed at the Science Museum in London.

Joseph Bramah died in 1814, never seeing his challenge overcome, but his son, Timothy, continued the business. [Future mentions of Bramah refer to either Timothy Bramah, Francis and Edward Bramah (his brothers who joined the business during the early 1820’s), or Bramah & Sons as a company]. Despite one failed attempt documented in 1817, Bramah’s Challenge Lock remained as a novel fixture gathering dust in their shop window.

Articles began to surface in the press about the shortcomings of some Bramah’s locks; it was stated that they could be picked by an exhaustive and methodical process of applying differing pressures to the individual sliders, thus freeing the barrel and allowing it to operate the locking bolt. In 1817, one of Bramah’s employees, William Russell, came up with the addition of false notches on all the sliders and the locking plate; this made it seemingly impossible for the lock picker to ascertain the correct pressures and settings to be applied in order to free the barrel. Russell’s false notches were added to all 18 sliders of the Challenge Lock! With most of Bramah’s box locks having between four and six sliders at that time, a lock fitted with 18 was surely impenetrable.

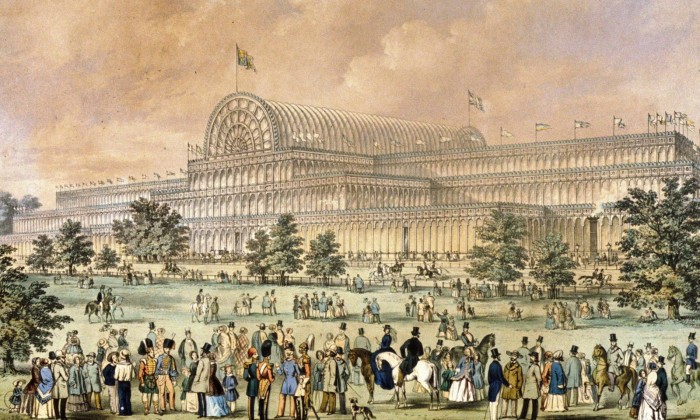

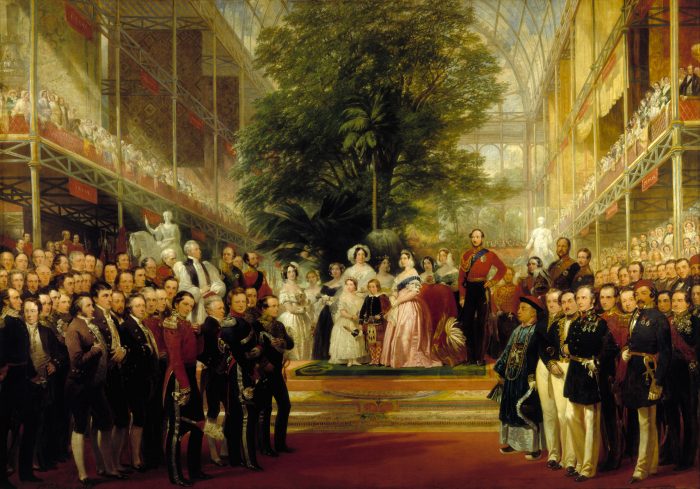

The importance and exclusivity of the Great Exhibition of 1851 attracted countries from all over the world to exhibit the finest examples of their work.

Interior view of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Day & Newell were a New York locksmith company that sent over their sales representative, Alfred Charles Hobbs, to present their ‘Parautoptic’ lock at the Great Exhibition [this lock went on to win a prize medal at the exhibition]. Not only was Hobbs an accomplished locksmith and inventor, he was also a very good salesman and indeed, showman. His thinking was that in order to promote their own lock [or more likely to promote himself], he should highlight the shortcomings and insecurities of those belonging to the competition; these being Jeremiah Chubb’s Detector lock and Joseph Bramah’s Challenge Lock.

Alfred Charles Hobbs (1812 – 1891).

Hobbs contacted the firm of Chubb on the 21st July 1851 announcing that he intended to pick their famed ‘Detector’ lock the very next day; the lock in question was fixed to an iron door of a vault within the Depository of Valuable Papers, in Westminster. Hobbs, as good as his bold words, unlocked Chubb’s Detector lock in only 25 minutes, then taking a further 7 minutes to relock it. Hobbs gained immediate celebrity status in the press, adding further to the pomp and circumstance of the Great Exhibition.

Front view of the internal mechanism of a Chubb ‘Definitive’ Detector lock from 1849.

Capturing the fascination and (somewhat reluctant) support of UK population, there was now only one more hurdle for Hobbs to overcome – Bramah’s Challenge Lock.

Prior to his Chubb Detector lock challenge, Hobbs had contacted Bramah on the 2nd July 1851 informing them of his intention to take on their challenge, and to request permission to make a wax impression of the lock’s keyhole in preparation.

A committee of three were appointed to manage and act as arbitrators for the challenge, with an agreement between Hobbs and Bramah drawn up on the 19th July 1851. It was stated:

- Hobbs had 30 days to open the lock.

- The lock was to be sandwiched between two pieces of wood and affixed to a wall (with sealed screws) in order to limit access to only the keyhole and hasp.

- The key would remain in the sole possession of Bramah at all times.

- The keyhole should be covered by an iron band, to be sealed by Hobbs, each time the lock is left unattended.

- If Hobbs was successful in picking or opening the lock, the key was to be used; if the key worked the lock as expected it would be accepted that the lock had been legitimately picked or opened, rather than by being forced and damaged.

Removing all potential grounds of suspicion associated with the interference of the lock during the challenge period, Bramah decided to relinquish the right to hold onto the key. Instead, Bramah recommended that the key be sealed away until either the culmination of the challenge or the 30 day period.

On the 24th July 1851, the Challenge Lock was removed from Bramah’s shop window and placed in one of the upper rooms where Hobbs, in isolation, began his seemingly impossible undertaking.

Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’ and key, manufactured by Henry Maudslay in 1790. Photo courtesy of the Science Museum, London.

Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’ and key, manufactured by Henry Maudslay in 1790. Photo courtesy of the Science Museum, London.

After a week having elapsed and with curiosity growing, Bramah wrote to the committee requesting that they attend their establishment in order to inspect Hobb’s progress. A reply to this request was received stating that all three members of the committee were in Paris, and although they would have liked to attend, they were not sure what use their inspection would serve. Upon hearing this, Bramah disallowed Hobbs from continuing his efforts until more clarity could be lent to this situation.

On the 8th August 1851, Bramah wrote to the committee again expressing their disappointment at their lack of attendance, and at not being granted the opportunity to see the result of the key operating the lock; even though Bramah had relinquished their rights to the key’s usage, they were in the belief that this wouldn’t exclude members of the committee doing so on their behalf. Bramah suspected that Hobbs would have likely damaged the lock to such an extent that the key would no longer work.

A meeting took place between Bramah and the committee on the 15th August 1851. Bramah requested that they take the opportunity to test the key in the lock, as well as enlist someone to remain present during the remainder of the challenge. The committee rejected both requests; they didn’t believe there was any value to testing the key until the conclusion of the challenge, or any necessity to have a person present during the process. They thought that if Hobbs did indeed damage the lock in any way, he had the right to repair it accordingly should the time limit allow.

As of the next morning, Hobbs was able to return to his task.

Bramah wrote to the committee on the 19th August 1851 expressing that they felt it would be impossible for their challenge to now be met in a fair and reasonable way so as to be able to offer the reward money; their reasoning being that the privacy afforded to Hobbs during the challenge prevented them from knowing if the lock had been opened and, if so, how the instrument in question was created and used. Bramah received no response to their letter.

On the 23rd August 1851, Hobbs, in the presence of two of the three committee members, displayed the Challenge Lock with its hasp open, then demonstrated its bolt moving back and forth. This seemingly impossible achievement had taken Hobbs over 51 hours of labour spread over 16 days.

On the 29th August 1851, now in the presence of all the committee members and Bramah, Hobbs again displayed the hasp of the Challenge Lock open. Attached to the wood surrounding the lock were several connected pieces of apparatus that kept a rod tightly pressed into its keyhole; the addition of a small, bent, handheld piece of steel enabled Hobbs to turn the barrel of the lock allowing the hasp to re-enter its socket. Hobbs also produced two further tools; one similar to a stiletto, and the other similar to a crochet hook. Bramah immediately requested that the key be tried in order to see if the lock had indeed been successfully picked and not just forced; this request was denied by the committee in order to allow Hobbs a further day to get the lock back into its original state. On the next day, the key was inserted and it operated the lock without issue.

Bramah’s ‘Challenge Lock’ and key with its hasp open.

The committee submitted their full report of the challenge on the 2nd September 1851, concluding:

“We are, therefore, unanimously of the opinion that Messrs. Bramah have given Mr. Hobbs a fair opportunity of trying his skill, and that Mr. Hobbs has fairly picked or opened the lock, and we award that Messrs. Bramah and Co. do pay to Mr. Hobbs the 200 guineas.”

Bramah responded to the committee by letter the very same day; they acknowledged the opening of their lock, yet made reference to their (ignored) letter from the 19th August 1851 echoing their concern regarding the eligibility of the reward money. Bramah believed it was only fair that the use of the key during this period would have reset the sliders and mechanism, therefore simulating normal use of such a lock. They expected that a worthy lock-picking tool would be able to pick the lock without the necessity of additional fixed apparatus that would be easily detected in a real world scenario.

Bramah deemed this challenge to have no practical purpose whatsoever; they were not informed about the method used to open the lock, or given any instrument that opened the lock [it is documented that Hobbs did formally produce several of his lock-picking instruments to the committee, however I wonder if Bramah were only willing to accept one single all-encompassing lock-picking tool? If this was their intention, this point could be fairly argued if we refer to the original challenge signage that Hobbs had initially responded to… “The artist who can make AN instrument …”] There was no information that Bramah could take away with them to help improve their locks – the apparent sole purpose of the original challenge.

With the 30 day period having expired, Bramah dismantled the Challenge Lock and noticed that although there was no concerning damage to the internal mechanism, some of the sliders had been significantly bent then re-straightened, with some others having been almost filed through.

In the 10th September 1851 edition of the Morning Chronicle newspaper, Bramah made the announcement that they had forwarded a cheque to the committee for the 200 Guineas, to be given [whether in good grace or not – the latter, I suspect] to Alfred Charles Hobbs as his reward for opening the Challenge Lock. This cheque was however accompanied by a letter outlining Bramah’s dissatisfaction and protest, also published in this same newspaper article as follows:

“We need scarcely repeat that the decision at which the arbitrators have arrived has surprised us much. We owe it to ourselves and the public to protest against it, and we do so for the following reasons: –

1. Because the arbitrators having been appointed to see ‘fair play,’ and that the lock was fairly operated upon, did not, although repeatedly requested in writing to do so, once inspect [an asterisk in the original text was inserted here with the following footnote: “Mr. Hobbs stated he preferred no one being present, as it made him nervous. If the operation was so delicate – what chance would a burglar have?” – Messrs. Bramah] or allow any one to witness Mr. Hobbs’ operations during the sixteen days he had the sole custody of the lock and was engaged in the work.

2. Because that arbitrators did not once exercise their right of using the key, although repeatedly requested in writing to do so, till after Mr. Hobbs had completed his operations, and then, instead of applying it at once, to prove no damage had been done to the lock, allowed him twenty-four hours to repair any that might have occurred.

3. Because the lock being opened by means of a fixed apparatus screwed to the woodwork, in which the lock was enclosed for the purpose of the experiment (which it is obvious could not have been applied to any iron door without discovery), and the addition of three or four other instruments, the sprit of the challenge has evidently not been complied with.

4. Because, from the course adopted, and opportunity of some good scientific results has been taken from us, as neither arbitrators nor any one else saw the whole, or even the most important instruments by which it is said the lock was picked, actually applied in operation, either before or after the lock was presented open to the arbitrators.

5. Because, during the progress of Mr. Hobbs’ operations, and several days before their completion, we called the attention of the arbitrators to what we considered the interpretation of the challenge, begging at the same time that they would apply the key, and appoint some one to be present during the residue of the experiment, feeling that, whatever might be the result in a scientific point of view, the reward could not be awarded. We would add that we think that several points which appear on your minutes should have been mentioned in your award, more especially that Mr. Hobbs, on the 2nd of June [I believe they meant the 2nd July], took a wax impression [an asterisk in the original text was inserted here with the following footnote: ‘This means as far as he could through the keyhole.’ –Messrs. Bramah] of the lock, and had made, as far as he could, instruments therefrom between that date and the commencement of his operations.”

Hobbs, not suffering from shyness or lack of showmanship, converted his 200 Guinea reward into gold sovereigns and, with a policeman standing guard, displayed them in a glass case on the Day & Newell stand at the Great Exhibition. His signage made it quite clear why this money had been rewarded, and this created a major stir amongst the attendees who wanted to see if this unbelievable story was true. His ego was likely even further boosted upon the announcement that the Bank of England were replacing all their Chubb Detector locks for Day & Newell’s Parautropic locks.

Despite Bramah being awarded a prize medal at the Great Exhibition, their reputation had taken a serious dent. They were pushed into a position where they had to defend their lock that had been so publicly exploited. Writing to the editor of the Morning Chronicle on the 10th October 1851, Bramah wrote,

“SIR, – This controversy having excited an unusual degree of public attention for some time past, perhaps you will be good enough to allow us to state in your journal that the lock on which Mr. Hobbs operated had not been taken to pieces for many years, and it was only on examining it (after the award of the committee) that we discovered the startling fact, that in no less than three particulars it is inferior to those we have made for years past. The lock had so long remained in its resting place in our window, that the proposal of Mr. Hobbs somewhat surprised us; after his appearance, however, no alteration could of course be made without our incurring the risk of being charged with preparing a test lock for the occasion. We were, therefore, bound in honour to let the lock remain as Mr. Hobbs found it when he accepted the challenge. No one inspected his operations during the sixteen days he had the sole custody of the lock and was engaged in the work. We are compelled to adventure another 200 guineas in order that we may see the lock operated upon and opened, if it be possible, and thus gain such information as will enable us to use means that would defy even the acknowledged skill of our American friends. We believe the Bramah lock to be impregnable, and we cannot open it ourselves with the knowledge Mr. Hobbs has given us. We have fitted up the same lock with such improvements as we now use, and some trifling change suggested by the recent trial, and restored it with its challenge to our window. [an asterisk in the original text was inserted here with the following footnote: “The lock remained in the window for four months expressly for Mr. Hobbs to make a second trial. He did not make the attempt: it was then only ‘removed to stop the idle applications of men and boys,’ which took up one person’s time to attend to.” – Messrs. Bramah.] We have not done this in a vain boasting spirit – on the contrary, we feel it rather hard that from the way in which the former trial was conducted we are driven to adopt this course – had any one inspected Mr. Hobbs’ operations during that trial it would not have been necessary.”

Maybe it could be argued that the best defence – and indeed advertisement – Bramah could put forth is that … an extremely accomplished locksmith took 51 hours to open a lock that hadn’t had its design updated for 34 years, under unrealistically perfect test conditions, using multiple tools and fixed instrumentation not subjected to the possibility of detection. This is surely a great credit to the ingenuity of Bramah and their achievements in lock manufacture.

How on earth did Hobbs beat those probabilities?

[I must pose the above question rhetorically, as I am simply at a loss to explain it … but here’s the official story] Behind closed doors there was no magic and no showmanship; Hobbs employed that same exhaustive and methodical process that had previously exposed the insecurity of Bramah’s pre-1817 locks. His process, as quoted from ‘Rudimentary Treatise on the Construction of Door Locks for Commercial and Domestic Purposes’ edited by Charles Tomlinson, reads as follows,

“The first point to be attained was to free the sliders from the pressure of the spiral spring; the spring was very powerful, pressing with a force of between thirty and forty pounds; and until this was counteracted, the sliders could not be readily moved in their grooves. A thin steel rod, drilled at one end, and having two long projecting teeth, was introduced into the keyhole and pressed against the circular disc between the heads of the sliders; the disc and spring were pressed as far as they would go. In order to retain them in this position, a curved stanchion was screwed into the side of the boards surrounding the lock, and the end brought to press upon the steel rod, a thumb-screw passing through the drilled portion of the instrument and keeping it in its place. The sliders being thus freed from the action of the spring, operations commenced for ascertaining their proper relative positions. A plain steel needle, with a moderately fine point, was used for pushing in the sliders; while another, with a small hook at the end, something like a crochet-needle, was used for drawing them back when pushed too far. By gently feeling along the edge of the slider the notch was found and adjusted, and its exact position was then accurately measured by means of a thin and narrow plate of brass, the measurements being recorded on the brass for future reference. The operator was thus enabled by this record to commence each morning’s work at the point where he left off on the previous day. The lock having eighteen sliders, the process of finding the exact position of the notch in each was necessarily slow. Mr. Hobbs employed a small bent instrument to perform the part of the small lever or bit of the key; with this he kept constantly pressing on the cylinder which moved the bolt. He thus knew that if ever he got the slide-notches into the right place, the cylinder would rotate and the lock open. He could feel the varying resistance to which the sliders were subjected by this tendency of the cylinder to rotate; and he adjusted them one by one until the notch came opposite the steel plate. The false notches added, of course, much to his difficulty; for when he had partially rotated the cylinder by means of the false notches, he had to begin again to find out the true ones.”

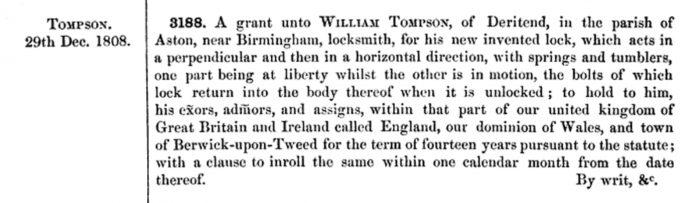

Tompson Patent Lock

William Tompson’s lock design was first patented on 29th December 1808. Its double-action movement is very similar to the earlier Turner Patent lock, whereby the bolt links and central moving peg initially raise beyond the surface of the lock plate, with then only the links sliding over to the left and into the locked position.

Tompson Patent locks are more often found in writing boxes; their design enables the lock plate surface to be flat and unimpeded when in the unlocked position. This differs from Bramah’s writing box locks which have their links and locating pins protruding through the lock plate surface whether in the locked or unlocked position.

The lock plate surfaces bear the name ‘Tompson’, usually accompanied by ‘Bir.M’ (short for Birmingham – the location of his manufactory) and ‘GR [George Rex] Patent’ beneath the monarch’s crown. These texts are laid out in a curved format, reminiscent once again of the Turner Patent lock.

Some Tompson Patent locks are fitted with a decorative cast brass front escutcheon; the keyhole of which is set within the design of the royal coat of arms, partially surrounded by ‘Tompson Patent’ in raised lettering.

Tompson Patent lock and key

Overhead view of a Tompson Patent lock plate stamped with ‘Tompson Bir.M’ (Birmingham) and ‘GR Patent’ beneath a crown.

Interior of a Tompson Patent lock (in its unlocked position) with the bolt, drill pin, circular ward and central moving peg in view.

Interior of a Tompson Patent lock (in its locked position) with the bolt, drill pin, circular ward, lever spring and central moving peg in view.

Interior of a Tompson Patent lock with the bolt removed. The drill pin, circular ward, two sprung levers and central moving peg are in view.

Operating a Tompson Patent Lock

- The key enters the front lock aperture; the side wards of the key tip are incised to clear the circular ward. The purpose of the circular ward is to obstruct any foreign key from operating the lock.

- As the key turns anti-clockwise, the bit to the key shank engages with the first sprung lever; this raises the bolt so that the links and the central moving peg simultaneously protrude from the surface of the lock plate.

- As the key continues its turn (from about the 12 o’clock position), it makes contact with the second sprung lever and carries the sliding bolt over towards the left; the pierced rectangular gating (the lanket) on the bolt allows the central moving peg to be independent and undisturbed by this sliding action, thus remaining fixed in place.

- The mechanism is now in its locked position.

- To unlock the mechanism, the key is re-inserted and turned clockwise by 360 degrees. The links and central moving peg fully retract to the same level plane as the surface of the lock plate. The key can now be withdrawn from the front lock aperture.

Acknowledgement of William Tompson’s lock patent taken from the ‘Titles of Patents of Invention Chronologically Arranged From March 2, 1617 To October 1, 1852’.

French Locks

French box locks manufactured during the eighteenth and nineteenth century are generally very simple mechanically speaking; many rely on, if not just one, only a few internal levers. The mechanism initially locks with one full anti-clockwise turn of the key but, unlike British locks, can then turn a further 360 degrees to essentially ‘double lock’ itself. The design of the internal lock bolt catered for this double throw action by having an elongated bolt arm. The reason for this double locking action is somewhat of an enigma as it doesn’t seem to enhance the overall security of the lock; one is left to speculate that it may serve to complicate and lengthen the work of the illegal lock picker.

An 1820’s French lock taken from an antique travelling box in Cuban mahogany. Note the elongated bolt arm (top left) to allow for the mechanism’s double throw action.

An 1820’s French lock in its ‘double locked’ position. Note the elongated bolt arm (top centre) to allow for the mechanism’s double throw action.

The addition of a ‘curtain’ (a revolving metal keyhole sheath that prevents multiple lock picking tools gaining access to the levers) and unusually shaped drill pins help make these locks extremely hard to open without their characteristic keys, adding certain complication for any lock picker or locksmith with the unenviable task of key duplication. Drill pins in the shape of a heart, triangle, star, (playing card) spade, and cloverleaf have been known to be fitted to these French locks.

Made significant by its usage on the magnificent 1787 and 1791 French ’Nécessaire de Voyage’ boxes commissioned by Marie Antoinette, the cloverleaf shaped drill pin is believed to symbolise the Christian holy trinity.

1806 French double action lock with cloverleaf (tréfle) shaped drill pin and surrounding curtain from an antique jewellery box in Cuban mahogany, by Georges Monbro.

French antique key with a cloverleaf (tréfle) shaped shaft.

French antique key with a cloverleaf (tréfle) shaped shaft.

1789 French lock with triangular shaped drill pin and surrounding curtain. Note the small prongs to the edges of the key hole; this requires a ‘Z’ shaped key bit to pass through it.

French lock fittings are externally recognisable by their cylindrical links to the top link plate and circular entry points to the main lock housing. These attributes, though subtle, weren’t found on British boxes which instead had cuboid links to the top link plate and rectangular entry points to the main lock housing.

Circular entry point to a French lock housing. The cylindrical link from the link plate engages here.

Cylindrical link on the top link plate.

Circular entry points to the lock housing, and a cloverleaf (tréfle) shaped lock drill pin and key from a French antique jewellery box in palisander wood.

It wasn’t uncommon for some French boxes to be fitted with English Bramah patent or Chubb locks, but their inclusion necessitated the customisation of the link plates and lock entry points accordingly.

Chubb Dectector lock from a French antique nécessaire de voyage dressing case in ebony with floral brass inlay by Aucoc Ainé à Paris.

Bramah patent lock from a French antique jewellery box in ebony with yellow and rose brass inlay.

French Box Design

The French ébénistes (cabinetmakers) enjoyed a reputation for the artistic and decorative expression they applied to their box manufacture; this being amplified, in the opinion of some, when compared to their more ‘reserved’ British counterparts. READ MORE

Asprey’s ‘Great Exhibition of 1851’ Dressing Case

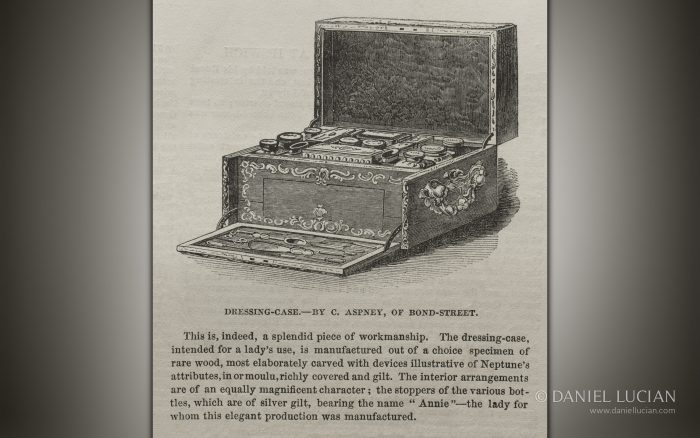

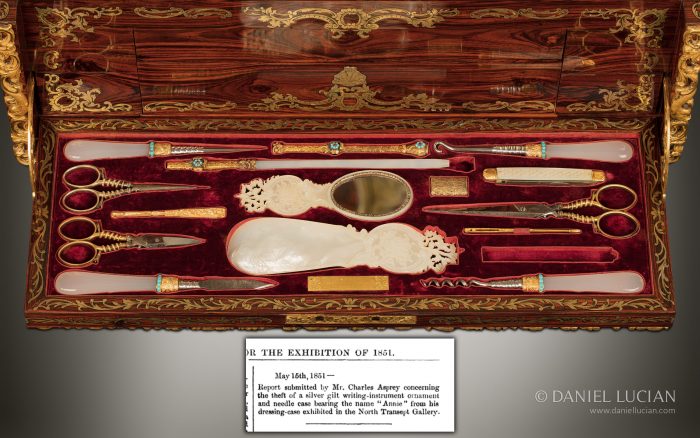

On public view for the first time since 1851, this magnificent dressing case was chosen by both Charles Asprey (I) and (II) to be displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park, London.

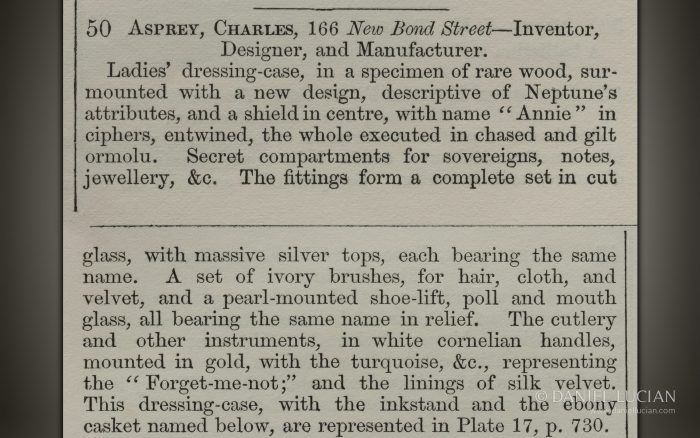

This large antique dressing case is veneered in Kingwood, retaining its original vibrant colour and finish. There are applied ormolu panels to the lid and front fascia of the case that depict Neptune and other mythical sea creatures. The two large ormolu side handles are in the design of fish, elaborately entwined. The centre piece to the lid bears the name ‘Annie’, belonging to Annie Gambart, the 16 year old wife of the famous Victorian art dealer, Ernest Gambart.

The interior of the dressing case is lined and ruched with its original claret red velvet. The interior rims are inlaid with a delicate brass foliate design accompanying the gilt engraved hinges and lock. The main compartment holds 13 heavy gauge silver-gilt topped, cut glass bottles and jars; these include four spring-loaded perfume bottles, two powder jars, two toothbrush jars, a soap jar, two lotion jars, a spring-loaded travelling inkwell, and a spring-loaded jar for liquids and creams. Additionally fitted are a silver-gilt perfume bottle funnel, pin cushion, match vesta/striker and nib blotter both in the form of bound books. All the interior pieces bear the matching ‘Annie’ cipher. The silver was manufactured by Thomas Diller and hallmarked London, 1848. The interior facing of the perfume bottles are engraved with, ‘Asprey – 166 Bond St’.

Silver-gilt bottles, jars and accessories with an overlaid foliate design and decorative ‘Annie’ cipher.

Close-up view of the overlaid foliate design and decorative ‘Annie’ cipher taken from a silver-gilt lidded jar.

The front panel of the dressing case drops forward to reveal a fitted tool tray to the reverse, as well as a brass plaque engraved with, ‘Asprey – Manufacturer – 166 Bond Street’. The set consists of a stiletto tool, button hook, corkscrew and nail file with handles of White Cornelian, mounted with gold and inset with turquoises, three pairs of gilt handled scissors with a design of entwined sea serpents around the handle shank, a gilt engraved retractable pencil and White Cornelian pen with a matching ‘Forget-Me-Not’ design of inset turquoises surrounding a ruby, a mother of pearl scaled penknife, a gilt engraved pencil lead case, a gilt engraved pair of tweezers, a gilt engraved ribbon threader, a fretworked mother of pearl shoe horn and matching miniature hand mirror bearing the ‘Annie’ cipher.

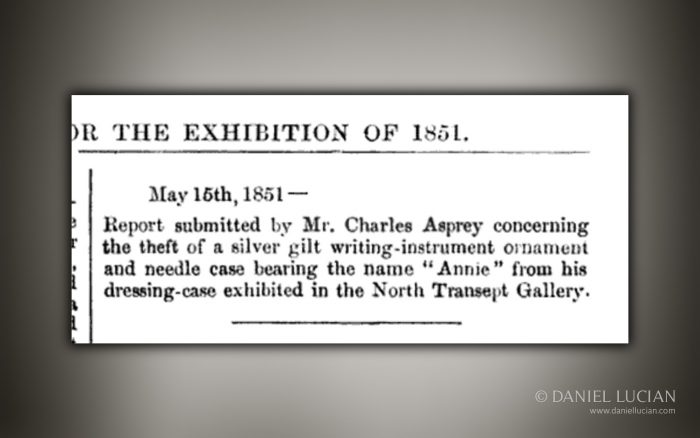

You will notice two small gaps in the tool tray; one would have been for the needle case, and the other would have been for the finial to the White Cornelian pen. Now why are these pieces missing? Taken from what seems to be a criminal activity report from the Great Exhibition, we read the following, ‘May 15th 1851 – Report submitted by Mr Charles Asprey concerning the theft of a silver gilt writing-instrument ornament and needle case bearing the name “Annie” from his dressing-case exhibited in the North Transept Gallery’.

Crime report submitted by Charles Asprey two weeks into the Great Exhibition.

Three pairs of gilt handled scissors with a design of entwined sea serpents around the handle shank.

A gilt engraved retractable pencil, pencil lead case, and white cornelian pen with a matching ‘forget-me-not’ design of inset turquoises surrounding a ruby.

A fretworked mother of pearl shoe horn and matching miniature hand mirror bearing the ‘Annie’ cipher.

The front fascia of the interior is inlaid with ornate engraved brass; a central cockle shell motif is hinged to act as a handle for the lower drawer. This lower drawer contains four ivory brushes, for hair and clothing, that have been carved with the matching ‘Annie’ cipher. Two smaller spring-loaded drawers, on either side of the lower drawer, are deployed by floor mechanisms beneath the rear left and right bottles in the main compartment. The spring-loaded upper drawer, lidded and velvet-lined for jewellery, can be released by pressing down on the middle screw from the engraved gilt brass plate to the rear rim of the dressing case.

View of the four deployed concealed drawers, three of which being spring-loaded. A central cockle shell motif is hinged to act as a handle to manually pull out the lower middle drawer.

Close-up view of the four deployed concealed drawers, three of which being spring-loaded. A central cockle shell motif is hinged to act as a handle to manually pull out the lower middle drawer.

The lower drawer contains four ivory brushes, two for hair and two for clothing. The two middle brushes are fitted ‘head to toe’.

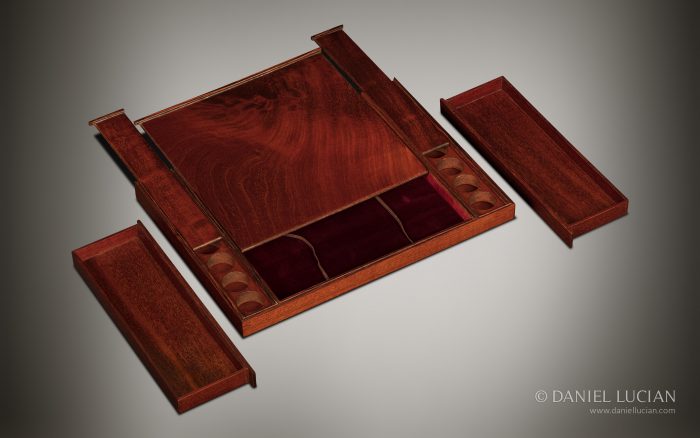

With the lower drawer removed, a concealed spring-loaded floor unit is accessible. This floor unit, made from solid Mahogany, is removed by pushing it backwards slightly, thus unlatching it and allowing it to pop up; it contains three slide-covered sections, two of which contain gold sovereign holders. With this concealed floor unit removed, two side mounted Mahogany spring-loaded drawers can be released from the very base of the dressing case.

Mahogany concealed floor unit containing three slide-covered sections, two of which containing gold sovereign holders. The two mahogany spring-loaded secret drawers are side mounted in the base of the box, only becoming accessible when the concealed floor unit is removed.

The ruched velvet panel in the lid can be released forward to reveal a secret letter wallet on the reverse, as a well as a sculpted mother of pearl handled face mirror fitted to the underside of the lid. The embossed, gold tooled mark onto leather reads, ‘Asprey – Manufacturer – 166 Bond Street’.

The dressing case is fitted with a Chubb Detector lock. This lock was designed to be impossible to pick or open without its dedicated key, whilst also having the ability to alert its owner to any unauthorised access attempts. The impressive gilt-brass key has been sculpted to portray the face of Neptune.

History and Provenance:

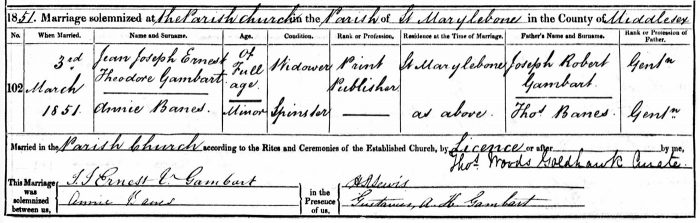

Being one of the first major dressing cases to begin its manufacture at Asprey’s then new 166 Bond Street address in 1848, the project was only finally completed in early 1851. It was purchased by Ernest Gambart (1814-1902) in 1851 as a wedding gift for his 16 year old wife, Annie Gambart (née Baines) (1835-1870).

Ernest Gambart was a very important, influential and indeed successful art publisher and dealer, responsible for transforming London’s art world. He created a platform to promote and sell art work on an international scale, introducing some of the finest foreign art work to the United Kingdom through regular exhibitions as well as from his own galleries. He worked with some of the most respected British and European artists of the time, to include Joseph Mallord William Turner, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Rosa Bonheur, Lawrence Alma-Tadema and William Powell Frith.

It was well documented that when Ernest first met Annie, he instantly became besotted with her, lavishing her with the finest jewellery, clothing and luxury items. They were married on the 3rd March 1851 at St Marylebone Parish Church, London. Shortly after this, the dressing case was loaned back to Asprey to be presented at the Great Exhibition.

Ernest and Annie Gambart’s marriage certificate from the 3rd March 1851.

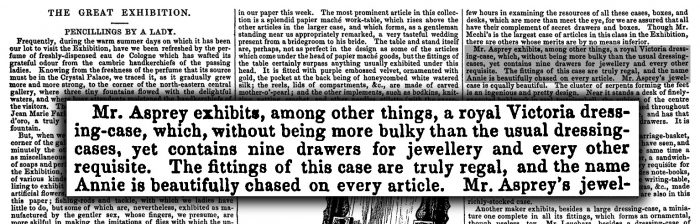

The Great Exhibition is considered to this day to be one of the most, if not the most important world exhibition of all time. Organised by Henry Cole and Prince Albert, it displayed and celebrated contemporary industrial technology, craftsmanship, art and design from over 15,000 national and international exhibitors. The venue, named ‘The Crystal Palace’, was an impressive 564 metre long, 138 metre wide cast iron and plate glass structure taking up 19 acres of London’s Hyde Park.

The exhibition was opened on the 1st May 1851 by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and ran for just over six months, before closing on the 11th October 1851. During this period, about six million people attended, making the exhibition a resounding success, whilst also creating a considerable profit; the proceeds of which helped to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, Science Museum, Natural History Museum, Royal Albert Hall, Imperial College, Royal College of Art, and the Royal College of Music.

Asprey received an ‘Honourable Mention’ for this dressing case by the board of judges at the Great Exhibition. Having only been in business in their own right for just over three years, this result immediately gained Asprey great admiration and recognition for the quality of their work, thus concreting the Asprey name to be synonymous with the utmost luxury and exclusivity to this very day.

It is believed that this box made its way back into Asprey’s own archives, held at 166 Bond Street, around 1867. This ties in with the year that Ernest split up from Annie, but also the year that Ernest moved his art gallery to the rear of Asprey’s shop located at 22 Albermarle Street; 166 Bond Street backed directly onto 22 Albermarle Street and, in 1861 Charles Asprey (II) purchased number 22, in order to join them and have shop fronts on two of London’s most exclusive streets.

Seemingly the dressing case remained in Asprey’s archives until the late 1960’s, where it was then purchased through the Asprey shop by a Canadian businessman as a wedding anniversary gift for his wife.

This exact dressing case features in the following publications:

‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’- Part III, Classes XI to XXX Manufacturers And Fine Arts. (Spicer Brothers, 1851). An Illustration and full description – (Plate 17, Page 791 & 793).

‘The Crystal Palace, And Its Contents; Being An Illustrated Cyclopaedia Of The Great Exhibition Of The Industry Of All Nations, 1851’. (W. M Clark, 1852). An illustration – (Page 284).

‘…For The Exhibition Of 1851’, May 15th 1851 (unknown title, page and publisher). A descriptive crime report from the Great Exhibition.

‘Illustrated London News’, May 3rd 1851. An Illustration – (Page 363).

‘The Lady’s Newspaper’, September 6th 1851. A Description – (Page 134).

‘Illustrated London News’, September 20th 1851. An Illustration and full description – (Page 381).

‘Directory of Gold and Silversmiths, Jewellers, and Allied Traders, 1838-1914’ by John Culme (ACC Art Books, 1987). Full description – (Page 17).

‘Asprey 1781-1981’ by Bevis Hillier (Quartet Books Ltd, 1981). Illustrations and full description – (Page 31, 32 & 33).

An illustration of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

A description of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

An illustration and description of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘Illustrated London News’, September 20th 1851.

An illustration of the Asprey dressing case taken from the book, ‘The Crystal Palace, And Its Contents; Being An Illustrated Cyclopaedia Of The Great Exhibition Of The Industry Of All Nations, 1851’.

A description of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘The Lady’s Newspaper’, September 6th 1851.

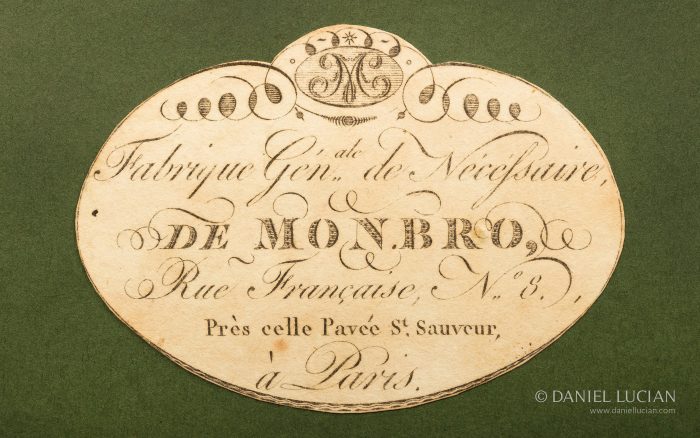

Monbro

Maltese born Georges Marie Paul Vital Bonifacio Monbro set up his business at 215 Rue de Beauregard (passage de la Boucherie), Paris in 1801. He quickly became recognised as a very skilled cabinetmaker (ébéniste), specialising in ’Nécessaire de Voyage’ boxes, and manufacturing for some of France’s most elite clientele.

Over the next forty years Georges Monbro moved his business around Paris six times; 8 Rue Française in 1806, Rue Bourg-l’Abbé in 1810, 5 Rue du Cimetière-St.Nicolas in 1811, 44 Rue Basse-du-Rempart in 1832, 32 Rue Basse-du-Rempart, and finally 2 Rue Boudreau until his death in 1841.

His son, Georges Alphonse Bonifacio Monbro, took over the business in 1838 continuing the great reputation associated with the surname. Shortly after his father’s death, the business moved to 18 Rue Basse-du-Rempart. George Jr, known as Monbro Ainé (Monbro the eldest), exhibited at the Exposition des Produits de l’Industrie in 1844 and the Exposition Universelle in 1855. By this time, the business was also known as Monbro Fils Ainé, and their first international retail establishment had been opened (in 1852) at 370 Oxford Street, London. Their international success lead to the opening up of a further premises on London’s Frith Street in 1861.

By 1870, Monbro Fils Ainé were based at Rue de l’Arcade 56, Paris.

Paper manufacturer’s label belonging to Georges Monbro, from 1806.

Edwards

David Edwards established his cabinetmaking business in 1813 based at 84 St James’s Street, London. He remained at this address for about a year, before moving to 21 King Street, Bloomsbury, London.

Gaining a great reputation for the quality of his work, David Edwards was appointed, ‘Writing and Dressing Case manufacturer to his most gracious Majesty’, soon after King William IV came to the throne in 1830. READ MORE

Wells & Lambe

John Wells was a pocket-book manufacturer based at 34 Cockspur Street. After his death in 1804, his two children, Thomas and Elizabeth Wells, having both apprenticed with him, continued the business under the name of J. Wells & Co. READ MORE

Turner Patent Lock

The Turner Patent lock, initially patented in 1798, can be disassembled into the following parts: READ MORE

Secret Compartments and Mechanisms

For centuries, secret compartments have been built into boxes and cabinets to hide their owner’s most valuable possessions, gold coins or private documentation. It wasn’t until the start of the 19th century that the inclusion of these secret, concealed compartments and mechanisms became more of an art form and a true symbol of a box maker’s ability and ingenuity. READ MORE

Maker’s and Retailer’s Marks

For the purposes of identification, advertising and acknowledgement, many boxes would bear the ‘marks’ of their maker’s and retailer’s. Their names, business addresses and details could be engraved or stamped into small brass plates or locks, gold-tooled and embossed into leather or velvet, engraved into wood or ivory plaques, or printed onto paper labels.

Sampson Mordan & Co

Sampson Mordan was born in 1790. After some years of apprenticeship, he established his own business in 1815, and joined forces with John Isaac Hawkins by 1822; together they filed a patent for a metal pencil with an internal lead propelling mechanism. Unlike the pencil’s popularity and longevity, their business relationship did not last much longer, with Mordan buying out Hawkins soon-after. READ MORE

Chubb Detector Lock

After counterfeit keys were used to commit a burglary at Portsmouth Dockyard in 1817, the British government issued a competition to create a lock that could only be opened using its own key. In response, Jeremiah Chubb designed the Chubb Detector lock, the principle of which was first patented in 1818. READ MORE

Leuchars Patent Bramah Lock

The Leuchars Patent Bramah lock was inspired by the same thought processes that created the Asprey Patent Bramah lock; to have a lock that could counteract the forgetfulness of its owner by not only automatically locking itself, but also allowing the box to be opened even if the key has been misplaced. READ MORE

Lund

Thomas Lund established his business and warehouse at 57 Cornhill, London in 1804. Initially selling pens and quills, Thomas had expanded the business by about 1815 to include the manufacture of cutlery, writing boxes and other fancy items, taking an additional premises at 56 Cornhill. READ MORE

The Great Exhibition of 1851

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, or simply the Great Exhibition, was created and organised by Henry Cole with the backing of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce and its president, Prince Albert.

The exhibition displayed and celebrated contemporary industrial technology, craftsmanship, art and design from over 15,000 national and international exhibitors. There was however an ulterior motive for setting up this exhibition; to promote and highlight to the world Great Britain’s position at the forefront of industry.

The venue, designed by Joseph Paxton, and named ‘The Crystal Palace’, was an impressive 564 metre long, 138 metre wide cast iron and plate glass structure taking up 19 acres of London’s Hyde Park.

The exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert on the 1st May 1851 and ran for just over six months. Indeed, Queen Victoria herself attended the exhibition on 33 different occasions. By the time of its closing on the 11th October 1851, the exhibition had welcomed over six million attendees. It was a resounding success and created a considerable profit of over £186,000 (approximately £24.5 million in today’s money); the proceeds of which, purchased 87 acres of land in London’s South Kensington, and helped to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, Science Museum, Natural History Museum, Royal Albert Hall, Imperial College, Royal College of Art, and the Royal College of Music

Renowned manufacturers, notably Asprey, Aucoc, Edwards, Leuchars and Mechi, exhibited their finest dressing cases. Prize medals for excellence of workmanship were awarded to Aucoc, Audot, Edwards, Laurent and Leuchars, with Asprey, Austin and Strudwick receiving honourable mentions.

‘The Crystal Palace’, venue of the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park, London.

Interior view of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

‘The Opening of the Great Exhibition by Queen Victoria 1 May 1851’ by Henry Courtenay Selous.

Refreshment area at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

An illustration of the Asprey dressing case taken from the ‘Official Descriptive And Illustrated Catalogue Of The Great Exhibition Of The Works Of Industry Of All Nations 1851’.

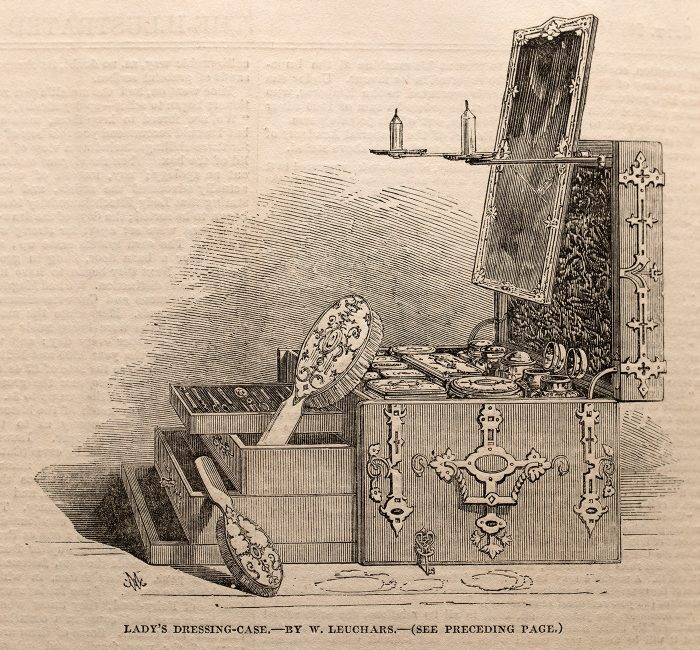

Lady’s dressing case by William Leuchars taken from the September 1851 edition of the Illustrated London News.

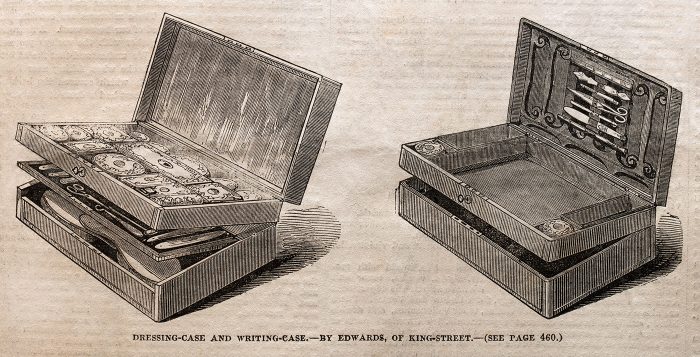

Gentleman’s dressing case and writing case by Edwards, entered into the 1851 Great Exhibition.

The International Exhibition of 1862

The International Exhibition of 1862, otherwise known as the Great London Exposition, showcased contemporary industrial technology, craftsmanship, art and design from 36 countries from around the world. It was organised by the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, and financed from the proceeds of the Great Exhibition of 1851 by the Royal Commission for the Exhibition 1851. READ MORE

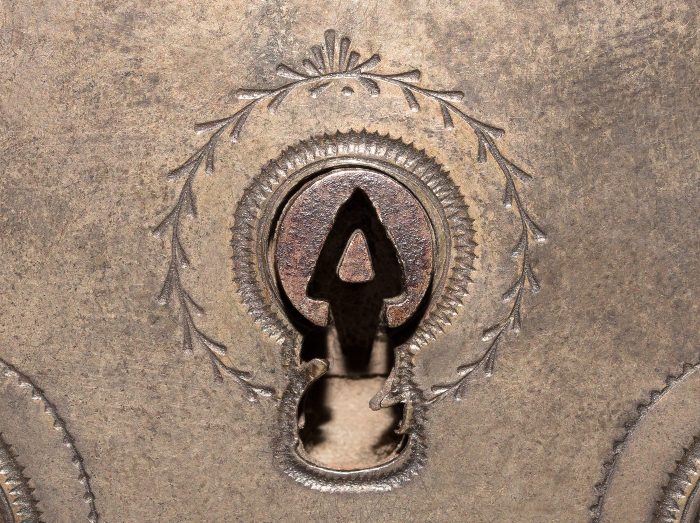

Velvet

Although documented as far back as the 8th century, velvet wasn’t introduced to Great Britain until the late 13th century.

Synonymous with royalty, nobility and the affluent, velvet was an expensive and highly desirable material due to its luxurious appearance, ability to absorb vibrant colour dyes, and its complication of manufacture. READ MORE

Thuya Wood

Thuya wood usually ranges in colour from a golden brown to a medium reddish brown. It has a characteristic three dimensional light and shade patterned appearance, accompanied by a multitude of small dark ‘eye’ formations. READ MORE

French Nécessaire de Voyage Contents

The Nécessaire de Voyage was an earlier French equivalent of the English dressing case, often more comprehensively equipped for travel. Larger sets could include kettles with heating burners, tea caddies, tea and coffee pots, cream jugs, sugar bowls, porcelain cups and saucers, sets of cutlery, drinking glasses, as well as sizeable items like silver wash basins, ewers, serving trays and removable candlesticks. READ MORE

History of the French Nécessaire de Voyage

The origins of the French travelling box date back to the late 14th century, with some of the earliest examples containing the most basic equipment for personal grooming. Over the centuries these boxes, most often the property of royalty, nobleman and other wealthy individuals, evolved from purely useful travel accessories into decorative and valuable luxury accessories. With these boxes gaining popularity, variations for toiletries, eating and drinking, sewing, writing, and other scientific purposes were manufactured. READ MORE

Dressing Case Tools and Accessories

Vanity and travelling tools were essential components of most dressing cases. Tools such as scissors, tweezers, nail files, retractable pencils etc, were often present in both ladies and gentlemen’s versions. Gentlemen’s dressing cases might also include cut throat razors, shaving brushes and boot jacks, whereas the ladies equivalents tended to incorporate sewing related tools such as needle cases, crochet hooks, bodkins and thimbles etc. READ MORE

Aucoc

Taking over from Pierre-Dominique Maire, the highly respected ‘Nécessaire de Voyage’ manufacturer, the company of Aucoc was started by Jean-Baptiste Casimir Aucoc in 1821. Based at 154 Rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, Casimir worked primarily a silversmith, his speciality also being in the manufacture of ‘Nécessaire de Voyage’ dressing and travelling cases. READ MORE

Index of French Makers and Retailers

Directory of French Nécessaire de Voyage and Nécessaire de Toilette manufacturers and retailers during the 18th and 19th Century. READ MORE

Dressing Case Bottles and Jars

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, dressing case bottles and jars tended to be plainer in appearance, with more emphasis on functionality and practicality. It was really around the Regency period that more attention began to be given to the glassware, as well as their lids and tops. READ MORE

Eras and Periods

Regency Period (1811 – 1820)

The Regency period began in 1811, when King George III was deemed unfit to rule Britain, and his son George, the Prince of Wales, took over as Prince Regent. It wasn’t until King George III died in 1820 that the Regency period ended. READ MORE

Morocco Leather

Morocco leather was considered one of the finest varieties of leather due to its suppleness and softness, as well as its strength and resilience. Initially sourced from Moroccan goatskin, later sources, whilst often still being referred to as ‘Morocco’ leather, also came from North African sheepskin and split calfskin. READ MORE

Index of Locksmiths

Directory of English locksmiths associated with antique dressing cases, antique toilet boxes, antique jewellery boxes and antique writing boxes. These listings have been kept specific to the Regency, late Georgian, William IV and Victorian era’s. READ MORE

Index of Silversmiths

Directory of English silversmiths associated with antique dressing cases. These listings have been kept specific to the Regency, late Georgian, William IV and Victorian era’s. READ MORE

Giroux

Maison Alphonse Giroux was established in 1799 by Francois-Simon-Alphonse Giroux, an art restorer, cabinet maker and one of the official restorers for the Notre Dame Cathedral. Based at 7, Rue du Coq-Saint-Honoré in Paris, the business initially started selling artist’s supplies, as well the products of his cabinetmaking work. The nature of the business soon expanded into the manufacturing and retailing of luxury goods and artwork, attracting the keen attention of french kings and members of the royal families. READ MORE

Bramah

Joseph Bramah started out by training as a cabinet-maker. In 1784, after attending some lectures on lock making, he patented his first lock and in the same year set up the Bramah Locks Company at 124 Piccadilly, London. READ MORE

George Davis Patent Lock

Based in Windsor, Berkshire, the lock maker, George Davis patented his ‘Double Chambered’ lock in 1799. READ MORE

Fretwork and Piercing

Fretwork is the cutting of intricate designs into wood, metal and other materials using a fretsaw. Fretsaws have a deep frame to allow for more mobility and less restriction when cutting into wider areas of material. The fine-toothed blade is short in comparison to the frame, which not only allows it to retain some strength, but also gives it more mobility and precision when working closer to the material for intricate work. READ MORE

Houghton & Gunn

William Houghton originally established his business in 1822. By 1841, he was based at 162 Bond Street, London. It wasn’t until 1868 that he went into partnership with Charles Henry Gunn. READ MORE

Halstaff & Hannaford

William Halstaff started his business in 1825 at 68 Margaret Street, Cavendish Square, London, later moving it in 1838 to 228 Regent Street, London as Halstaff & Co. READ MORE

Ebony

Ebony is a very dense, dark wood that can vary from a dark brown to a black colour. Its species can be found in and around India, Africa and South East Asia. READ MORE

Thornhill

The company of Thornhill can be traced back to a cutler named Joseph Gibbs in 1734, based at 137 Bond Street in London. By 1772, the business was in the hands of his son, James Gibbs, and in 1800, was renamed as Gibbs & Lewis. By 1805, the business was being run by John James Thornhill and John Morley, under the name of Morley & Thornhill. They moved to 144 New Bond Street, London in 1810. READ MORE

Monograms, Crests and Emblems

Monograms

A monogram is a group of two or more letters, overlapping or intertwining one another to form a design or symbol. They usually represented the initials of the family’s or individual’s name. READ MORE

Betjemann Patent Mechanisms

From 1859, based at 36, 38 & 40 Pentonville Road, London, George Betjemann and his two sons, George William Betjemann and John Betjemann, started to take the art of cabinet and box making to new creative heights. Under the business name of George Betjemann & Sons, they began to patent their innovative and ever-evolving designs and mechanisms. Specific to their range of ‘extending’ or ‘expanding’ dressing cases and boxes, there were two particularly impressive types of patented mechanism – the ‘Automatic’ mechanism and the ‘Angle-Wing’ mechanism. READ MORE

Index of British Makers and Retailers

Directory of British antique dressing case, antique toilet box, antique jewellery box and antique writing box manufacturers and retailers. These listings have been kept specific to the Regency, late Georgian, William IV and Victorian era’s. READ MORE

Mirrors

The inclusion of mirrors in dressing cases was almost a prerequisite. Removable mirrors would be stowed in the lid of the box and with some having their own fold out stands, could be placed on a dressing table or other surface. READ MORE

Cut Glass

The method of sculpting and cutting decorative designs into glass was achieved by the use of a Copper Wheel Crystal Engraving Lathe. A vast array of spindled copper and stone grinding wheels of varying size and form could be attached to the lathe to create the desired cut-glass incisions. READ MORE

Price On Application

Price On Application