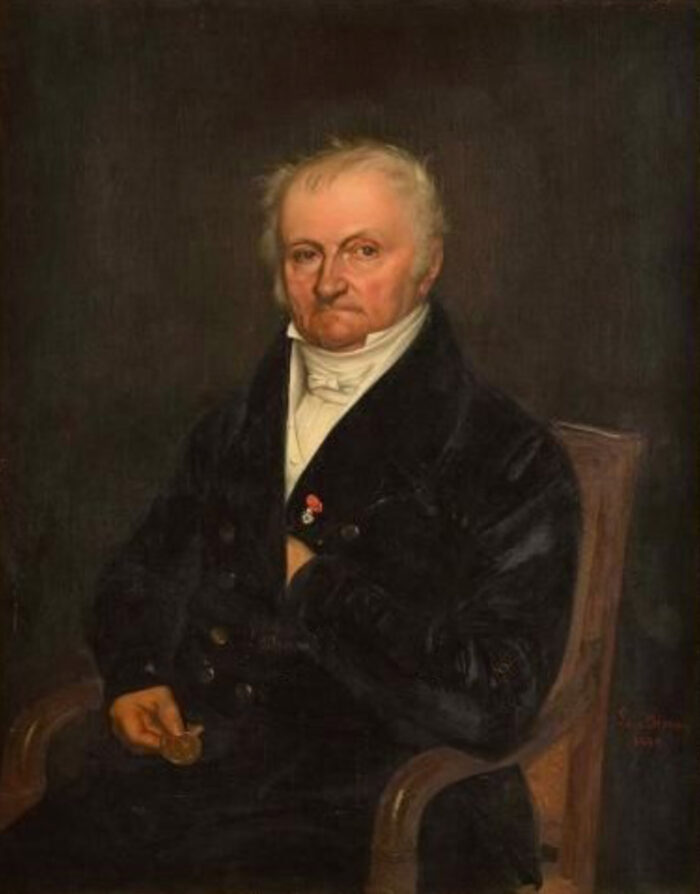

Martin-Guillaume Biennais

Martin-Guillaume Biennais was born in the Normandy region of La Cochère, France in 1764. His early years were dedicated to training as a craftsman, before moving to Paris at the age of 24. There, he specialised as a tabletier (a manufacturer of small luxury and decorative items from wood or ivory), an ébéniste (a cabinet-maker, particularly working with Ebony) and an orfévre (a goldsmith).

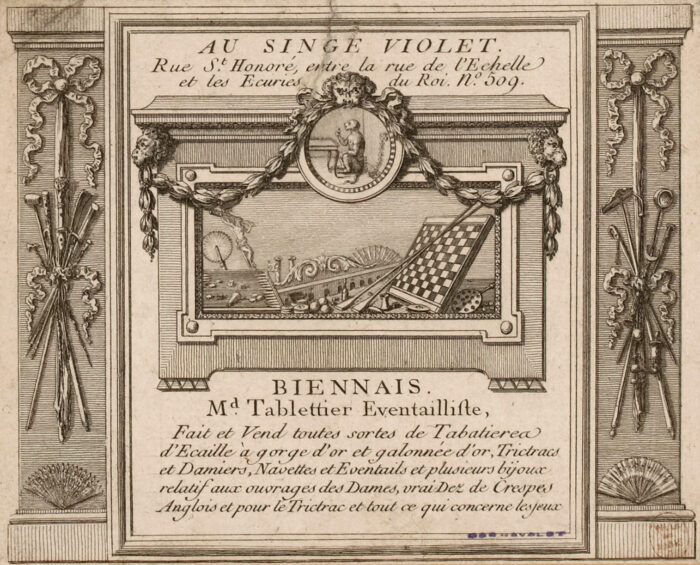

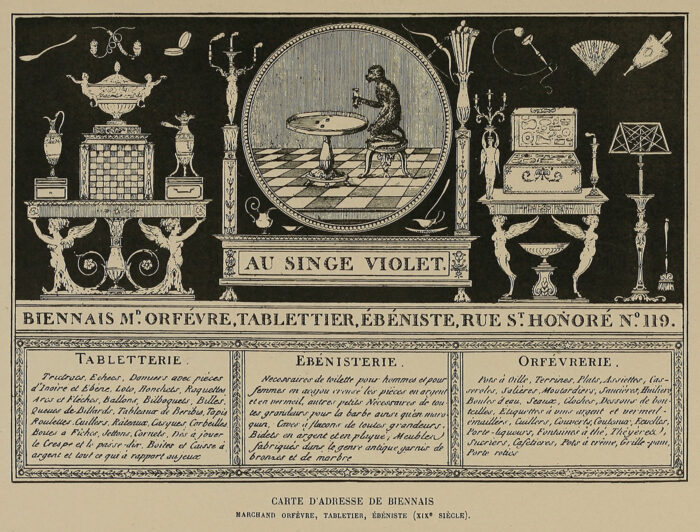

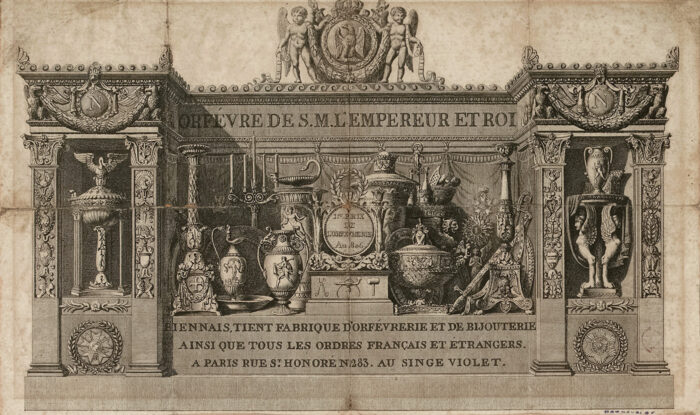

In 1789, Biennais set up his own establishment at Au Singe Violet (at the [sign of the] purple monkey), 509, 510 & 511 Rue Saint-Honoré, Paris. In 1790 the shop numbers were changed to 119 & 121 Rue Saint-Honoré, then changed again in 1805 to 281 & 283 Rue Saint-Honoré.

One of Biennais’ particular specialities was the manufacture of travelling nécessaire boxes, often crafted from solid mahogany; he employed freelance silversmiths to populate their interiors with bottles, jars and all manner of ‘necessary’ tools and instrumentation to accompany their owners during travel. At this time, the demand for luxury goods was very minimal, but Biennais’ work supplying nécessaires to French army officers reliably sustained his business. With the dissolution of workers’ guilds and associations under the Le Chapelier Law of 1791, merchants and artisans were now allowed to work as individuals free from their former practice restraints; as a result, Biennais expanded his business repertoire by being able to manufacture and certify silver items in-house.

In 1798, just prior to Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign to Egypt and Syria, Biennais supplied Napoleon with some nécessaires on credit with the agreement that the debt was to be repaid upon his return. As good as his word, Napoleon did indeed pay what he owed. Whilst the work of Biennais was exceptional in its own right, it seems that the faith and trust he exhibited towards Napoleon also favoured him well; in 1804, Biennais was made the imperial goldsmith, supplying the crown, sceptre and other ceremonial adornments for Napoleon’s coronation in December of that same year.

At the height of his success, having built up an exclusive client base to include the French imperial and royal family, the King and Queen of Holland, the King of Westphalia, and the royal households of Russia, Austria and Bavaria, Biennais was employing nearly 200 artisanal workers.

In 1819, Biennais retired, leaving his business to his former apprentice, Jean-Charles Cahier.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais died at his home in Paris in 1843 at the age of seventy-eight.

Today, the magnificent works of Biennais are rare, but can be found in some of the most renowned museums, royal households, stately homes and private collections around the world.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais (1764-1843).

Martin-Guillaume Biennais advertisement/ letterhead from 1789 within his first year of business. Note the address number of 509; the shop numbers were changed to 119 & 121 in 1790, so we are able to accurately date this.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais advertising business card from circa 1795.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais invoice letterhead from 1805.

Martin-Guillaume Biennais invoice letterhead from 1811.

This is largest of all Napoleon I’s nécessaires manufactured by Biennais around 1802. The silver-gilt contents had originally been engraved with a ‘B’ for Bonaparte, but this was replaced with the Emperor’s coat of arms in 1807.

Necessaire de voyage belonging to Napoleon I, manufactured by Martin-Guillaume Biennais.

Price On Application

Price On Application